MUSIC REVIEW BY DUNCAN HEINING, All About Jazz

5-STARS Lenny Bruce might have skewered it with his skit, "Psychopathia Sexualis." Mike Myers' mildly misogynist poet might have parodied it in the movie I Married an Axe Murderer (1993). It has been dismissed as a late-fifties fad associated with the Beats. And, yet, the desire of poets and jazz musicians to combine their art forms has proven surprisingly durable.

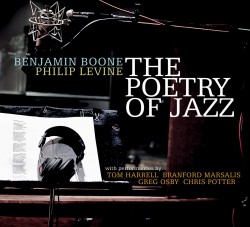

Sometimes, the practice is just plain embarrassing and made worse by the reality that those involved, like the man with no shorts and his zipper open to the world, simply haven't realized it. But sometimes it works, and when it does it becomes something much more than the sum of its parts and touches us emotionally in wholly new ways. And it most certainly works with Benjamin Boone and Philip Levine's The Poetry of Jazz. In fact, the record can easily be described as a master class in the combining of different art forms—and not just poetry and music.

The key as Boone explains below involves finding ways of making the voice and words part of the music. Music and spoken word have to be equal partners and that necessitates a mutual respect between poet and musicians and for their respective art forms. Listening to "Yakov," a tale of friendship, loss and migration, one hears how Boone's soprano replies on and responds to the emotional quality and weight of Levine's voice, while a steady ostinato from the rhythm section holds both suspended—an essay in complementarity.

But then Levine and Boone trade words and lines on the angry frustrations expressed in "They Feed They Lion," caught in a call-and-response of equal but personalised power and authority. And complementarity can also involve questioning and querying and even challenge. Boone's setting of the long and difficult "A Dozen Dawn Songs, Plus One" illustrates this perfectly. This is an essay in contrast, as Levine's voice and words struggle to express and escape the drudgery of the production line, the music's unremitting pulse and screaming soprano remind the listener of the reality of the day-in-week-out grind.

The word is "prosody." We experience this in early infancy in our parent/care-giver's soothing voice. The language that parents use to sing-talk to a baby is called "motherese." Meaning is not important in that context. But the tone of voice is crucial. It holds us in its embrace. That is "prosody." Through that, we begin to learn how to become attached to others and begin the shift from "his (sic!) majesty the baby" —to use Freud's wonderful phrase—to become a social being aware of others and our connectedness to the world. And, as adults, "prosody" remains an important element in the way we process all forms of communication. Even though we now have language skills to negotiate semantic meaning, prosody allows us to experience the emotional content of what we are hearing. Whatever my doubts about St. Paul, he knew what he was talking about in his first letter to the Corinthians.

Poets use the word prosody to describe rhythm and intonation. Developmental psychologists and linguists use the word with a slightly different emphasis to explain its part in the acquisition of language skills. However, it is in the area defined by the word prosody that success—or failure—in combining poetry and jazz may lie.

Charles Mingus understood this when he recorded with the great African-American poet Langston Hughes withThe Weary Blues (MGM 1958). Jayne Cortez clearly demonstrates such qualities on her recording with bassist Richard Davis in Celebrations and Solitudes Strata East, 1974) and with her group the Firespitters on Taking The Blues Back Home ( Verve 1996), as did Gil Scott-Heron on "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised" and "B-Movie." And Kenneth Rexroth's Poetry and Jazz at the Blackhawk (Fantasy 1958) and Kenneth Patchen's Kenneth Patchen Reads with Jazz in Canada (Folkways 1959) clearly got it.

The Poetry of Jazz is at times angry, "They Feed They Lion" and "A Dozen Dawn Songs, Plus One." At others, it is tender and genuine without sentimentality as on "The Music of Time" and on the gorgeous "I Remember Clifford" with the sumptuous fluegelhorn of Tom Harrell (surely Clifford Brown's heir apparent on this planet) and les fils Boone (Asher and Atticus) providing additional brass support. The Poetry of Jazz has those same attributes in spades. Complementarity and congruence between the emotional tone of voice and music and their semantic content.

True there are fine guest performances to enjoy—Chris Potter on "The Unknowable (Homage to Sonny Rollins)," Greg Osby on "Call It Music (Homage to Charlie Parker," Branford Marsalis on "Soloing (Homage to John Coltrane)" and let's hear it again for Tom Harrell! But the stars here are Philip Levine's words and Benjamin Boone's totally assured and apposite compositions and arrangements. Indeed, some of these settings are achingly beautiful, such as "By the Waters of the Llobregat" with its simple, limpid piano accompaniment and the baroque-like "Our Valley." Poetry and jazz just grew up.

All About Jazz: How did you come to record The Poetry of Jazz with Phil Levine, America's poet laureate?

Benjamin Boone: "My writer friend, Danny Foltz-Gray, introduced me to Phil's work in the year 2000. I was applying for a faculty position at California State University Fresno and he said, "Fresno? My absolute favourite living poet teaches there, Philip Levine!" So, I checked out Phil's work and there was an immediacy and a relevance to it that spoke to me. It speaks of the working class, of toil and drudgery, genocide, race relations, and what work truly is. And when I listened to him read I could hear the musicality of his voice—his phrasing and rhythm and melodies. My doctoral dissertation had been a musical analysis of speech and I could certainly hear music in Phil's recitations.

"A little later, I was asked by a local film society to play at fundraiser where Phil was also asked to perform. I called him and we decided to collaborate. The reviews were stellar and people kept asking when we would perform again. So, we decided to see what would happen if we honed the pieces and recorded them. That experiment was a success, so over the next several years—almost right until his death—we recorded twenty-nine of his poems with music.

AAJ: The title of the album—The Poetry of Jazz—suggests that your aim was to bring about a correspondence between the sound of the voice/poetry and the music. How did you go about composing music that would match both Levine's lines and his remarkably compelling performance?

BB: "You are correct—creating a correspondence between the sound and meaning of the poetry and the sound and emotion of the music was our primary intent. The producer, Donald Brown, and the engineer, Mike Marciano, and I discussed this at great length—how to make it so that the voice was a member of the band. It didn't work at first by any means. I had to re-write all of the initial pieces we performed together on that first concert. It took time for us all to figure out each other's pacing and phrasing. But Phil caught on amazingly quickly.

"It was actually a fun process for me because I've studied words and the sounds of words since I was young. Because of some hearing issues I have that make it hard for me to understand words, I tend to focus on speech melody. Also, my older brother, Joseph A. Boone, is a literary scholar and both he and my mom read to me voraciously and instilled a love of language from an early age. Then in grad school, when I was composing art songs, operas, and musicals, I had to really think about the relationship between the vocalist and the musicians. So, I studied how great composers like Puccini approached the voice. I learned you have to leave sonic space for voice in the frequency spectrum and you have to be careful about what types of musical activity you do behind the voice without destroying the intelligibility of the words. So yes, I was really careful about when, where and how the voice was used."

AAJ: Often with music/spoken word projects, one feels that one or other suffers at the expense of the other, but that is not the case here. What were the practical issues involved for you and the group in the studio with Levine and how did you address these?

BB: "I'm delighted you feel a synergy between the words and the music and that they are equal partners. In fact, when I first knew I would be collaborating with Phil, I investigated several recordings of poets with musicians. I dug many of them, but to my musical ear, often the music was mostly reacting to the surface-level action of the poems—doing "word painting." In others, it sounded to me like the music was only an underscore to the reading. I know many people like many of these collaborations but it's not that interesting to me as a composer or a performer. So, I started thinking about how a classical composer might approach the voice.

"I decided early on that if I were to do this, my self-imposed challenge would be to find a way music could enhance the central meaning of each poem and have the music be an equal partner in communicating that emotion. The listener would have to experience the words in a different way than if it were a reading. Otherwise, what would be the point? One of my thoughts was that music can give the listener time to contemplate what they have heard—time for it sink beneath the surface—time for the listener to feel on a deeper level what is being expressed. This is especially true in poems like "By the Waters of the Llobregat," which is about genocide, or "What Work Is," which is about lost opportunities or "A Dozen Dawn Songs Plus One," which is about the horrid existence of workers. If the music doesn't enhance the poem and give it added value in some real, emotional way, and serve as an equal partner, then to me it's not as artistically interesting—at least for the duration of an entire CD.

"And, of course, there were issues about how we went about accurately capturing Phil's voice in the studio. Maximus Media Studio in Fresno, CA is well-known for its voice-over work. They really know how to record voice and that is a primary reason we recorded there. In the studio, Phil was in an isolation booth but with a giant window into the main room where the rest of the band was set up. His room was big and had wood floors and walls and that gave a warm natural reverb. Phil and I had spoken about the poems and how to read them, where to pause and so on. But we never rehearsed with the band. Instead, he asked that I indicate on the printout of his poems where he was to start, pause or resume and for how many seconds. Most of the time, I just gave him a visual cue—like a conductor. Phil was a huge jazz aficionado all of his life and part of what you are hearing is Phil's innate ability to hear and work with the band, as if he were a musician himself. His ability to hear when the piano fill was done or when the drum was cuing a new section or when the band was building or changing the feeling was incredible. He was intuitive and really got it. That is really the magic on these recordings. Take his reading of "Gin" -it's the first take. In fact, all are either first or second takes. Amazing."

AAJ: The subject matter of many of the poems here talk about jazz and musicians that Levine got to hear in person—"I Remember Clifford," "Unknowable" (an homage to Sonny Rollins), "Soloing" (a tribute to John Coltrane), "Call It Music" (about Charlie Parker's sad experiences in California but also remembering trumpeter Howard McGhee) and several others. Were these your choices or Phil Levine's and how far did you influence the selection of the poems to record?

BB: "Most were my choices but not all. I certainly wanted to record Phil's poems about the jazz legends you just mentioned—I mean, how cool is it that Phil knew Howard McGhee? Howard told him about Parker—and also his poems alluding to music in some way. But there were other poems that just spoke to me because when I read them I heard music. Or more accurately, when I heard Phil's voice in my head reading them, I heard melodies or how music could add to the overall emotional quality of the poetry. I am thinking of "Our Valley," which creates such a timeless sense a space when you read it. It begged for a music that captured this feeling of heat, space and expansive timelessness. It's also about the Valley in which I live, so I knew exactly what he was describing. "Gin" is just hysterically funny and poignant. I couldn't not do it.

"As the project progressed, Phil started suggesting poems as well, poems he hadn't read in public yet or ones that had not been collected. Before one of the later sessions he sent me this mail, saying, "Here is a long poem in sections, short ones. I've never even read it; it appeared somewhere about 2 years ago. It wants music." Attached was "A Dozen Dawn Songs, Plus One," which is really long, with the setting changing frequently.

"Now that presented a difficult compositional challenge. The poem is heavy to digest -"piss-speckled snow," Even the rats sense the perfume of things to come. At its core, it speaks of helplessness, oppression, and relentless hardship. How can that feeling be sustained over the entirety of this long poem and not turn the listener off? How can I create the feeling of being in an oppressive factory or a dingy sub-standard apartment or a shattered life?

"I was reminded of Ravel's Bolero, where one idea keeps intensifying for about fifteen minutes. I took this as my model and started with no pulse, then with a rhythmically complicated ostinato figure over which I then add industrial-type sounds. So at the beginning you hear a screech (a stick raked across a cymbal), then the low strings of a grand piano hit with the palm of a hand as the sustain pedal is depressed. The machine-like scratching sound at the beginning is a credit card being raked across dampened piano strings. Listen and you can hear that the groove never really changes—it is relentless throughout, like in Bolero, and the melody doesn't arrive until near the end. It was an experiment in using limited musical material and stretching it for a long time. I am hoping Ravel would have been proud.

AAJ: It is hard to pick out a standout track but "Yakov," a lovely tale of friendship and loss, "They Feed They Lion," the high drama of "The Waters of the Llobregat" and "I Remember Clifford" represent quite special achievements. Yet each track is very different.

BB: "I appreciate that. I like these settings, too. "Yakov" is indeed about friendship and loss but also about how we view immigrants in this country and is really relevant today. That's one of the reasons I wanted to set this poem. In fact, we have recorded an instrumental version of "Yakov" that will appear on Volume II, which will be out in January 2019. We also have an instrumental coming out on Volume II of "They Feed They Lion."

"They Feed They Lion" is my writer friend's favourite Levine poem. He suggested I set it. It's about a race riot that happened in Detroit but it could be about any of the horrid racist events in the USA going on even now. Phil said he wanted to record this with a much different tone than he had used in the past. This was about the time the Black Lives Matter movement was starting. He wanted it to be angrier than prior readings and to sound almost like a preacher.

"Phil gave only small bits of guidance about the setting of his poems. He said the music for "Unholy Saturday" was too slow. So, we didn't record it. He asked whether I really wanted to record a poem as long as "Call It Music." I did. He also didn't like a guitar part, which we then cut out. But he did give clear direction—probably more than for any other poem—for "They Feed They Lion." In an email of August 13, 2012 he wrote:

"I've been thinking about how best to do "They Lion." I settled on a strategy of going in the opposite direction from what's been done in the past. Let the poem be . . . what?. . . violent? attacking? brutal?... & the music fairly calm until the pause before the storm of the final stanza. And then the horn continues into the final stanza—that would be the only time the horn & the poem are heard together. Have a break after each stanza of say half a minute or less, a break without fireworks but with mounting intensity, & then GO! In the breaks between stanzas, the horn answers the reading voice of the previous stanza."

"So, I changed the arrangement I had made, cutting out a contrasting section and saving the melody for the final climax. We recorded this at the very end of the session and Phil's voice was tired. He almost didn't record it. He was exhausted, not feeling well, and had said it was time for him to go home. But then he looked at the list of the tracks and saw "They Feed They Lion" was next and decided to stay and record it. That took tremendous energy. What you hear is his passion and vigour.

""The Water of the Llobregat" is such a heavy poem. How do you write music for a poem about genocide? I decided that the listener needed the time and space to process the depth of the words, to let them sink in deep. So, I used lots of space—long sustains in the piano, lots of time between phrases, spread out and uncluttered chords, flexing the tempo, until near the end when it becomes dissonant and relentless. We hoped each piece would create a unique sound world in which the poem could reside.

AAJ: The Poetry of Jazz features several guest performances—Chris Potter on "Unknowable," Branford Marsalis on "Soloing," Greg Osby on "Call It Music" and, perhaps best of all, the wonderful Tom Harrell on "I Remember Clifford." What is it about these particular musicians that made you choose them for these particular tracks?

BB: "I recall listening to what I thought was the final version of "I Remember Clifford" about trumpet legend Clifford Brown. I heard myself playing the melody on saxophone, and I thought, 'It's just wrong for me, a saxophonist, to be taking the lead on this track.' So, my producer-extraordinaire Donald Brown got Tom Harrell, who was deeply influenced by Brown, to do it.

"That logic extended to Chris Potter, who gets the big sound of Sonny Rollins, replacing my playing on "The Unknowable" about Rollins' hiatus from the public eye. Greg Osby, who sounds like what Charlie Parker would have sounded like had he lived longer, replaced me on "Call It Music," a poem that recounts a story related to Levine by his teacher, Howard McGhee, the trumpeter at the famed Dial recording session of "Lover Man," where Parker was intoxicated. And lastly, Branford Marsalis, who I knew through a connection with the New Century Saxophone Quartet's Steve Pollock, recorded "Soloing," in which Levine compares his aging mother's isolated existence to a Coltrane solo.

"It was tempting to have these jazz greats play on more than one track, but that would have defeated my primary reason for having them, namely to make the "homage" tracks special. I used a number of other musicians to help each track sound unique, like pianist, Craig von Berg, who you can hear adding crazy piano sounds to "A Dozen Dawn Songs Plus One." German violinist, Stefan Poetzsch, contributes to both "Dawn Songs" and "Our Valley," while Karen Marguth added vocalizations to "Gin" and "Music of Time." My two sons, Atticus and Asher Boone, joined me to form the backup 'horn section' on "I Remember Clifford." and trumpeter Max Hembd added harmony parts on several tracks."

AAJ: What is it for you that makes Phil Levine's performances here quite so powerful, so transcendent?

BB: "Well, I think it's pretty simple. Phil's voicing, timing, inflection, articulations, tempo, dynamics and just his ability to jam with the band was unparalleled. That allows the listener to hear and feel his poignant, powerful, easy to grasp and immediate poetry. The listener gets the point and it is deep, while the music grants them the time to process it and helps guide the poetic narrative. The topics are as relevant today as they were when he wrote them. Sadly, my guess is they will always be. Phil's words speak of truths inside all human beings—universal feelings we often repress or tamp down or simply don't recognize. His poetry allows us to let them in, to feel them and to see beyond ourselves. It's timeless and, as you say, transcendent."

Sometimes, the practice is just plain embarrassing and made worse by the reality that those involved, like the man with no shorts and his zipper open to the world, simply haven't realized it. But sometimes it works, and when it does it becomes something much more than the sum of its parts and touches us emotionally in wholly new ways. And it most certainly works with Benjamin Boone and Philip Levine's The Poetry of Jazz. In fact, the record can easily be described as a master class in the combining of different art forms—and not just poetry and music.

The key as Boone explains below involves finding ways of making the voice and words part of the music. Music and spoken word have to be equal partners and that necessitates a mutual respect between poet and musicians and for their respective art forms. Listening to "Yakov," a tale of friendship, loss and migration, one hears how Boone's soprano replies on and responds to the emotional quality and weight of Levine's voice, while a steady ostinato from the rhythm section holds both suspended—an essay in complementarity.

But then Levine and Boone trade words and lines on the angry frustrations expressed in "They Feed They Lion," caught in a call-and-response of equal but personalised power and authority. And complementarity can also involve questioning and querying and even challenge. Boone's setting of the long and difficult "A Dozen Dawn Songs, Plus One" illustrates this perfectly. This is an essay in contrast, as Levine's voice and words struggle to express and escape the drudgery of the production line, the music's unremitting pulse and screaming soprano remind the listener of the reality of the day-in-week-out grind.

The word is "prosody." We experience this in early infancy in our parent/care-giver's soothing voice. The language that parents use to sing-talk to a baby is called "motherese." Meaning is not important in that context. But the tone of voice is crucial. It holds us in its embrace. That is "prosody." Through that, we begin to learn how to become attached to others and begin the shift from "his (sic!) majesty the baby" —to use Freud's wonderful phrase—to become a social being aware of others and our connectedness to the world. And, as adults, "prosody" remains an important element in the way we process all forms of communication. Even though we now have language skills to negotiate semantic meaning, prosody allows us to experience the emotional content of what we are hearing. Whatever my doubts about St. Paul, he knew what he was talking about in his first letter to the Corinthians.

Poets use the word prosody to describe rhythm and intonation. Developmental psychologists and linguists use the word with a slightly different emphasis to explain its part in the acquisition of language skills. However, it is in the area defined by the word prosody that success—or failure—in combining poetry and jazz may lie.

Charles Mingus understood this when he recorded with the great African-American poet Langston Hughes withThe Weary Blues (MGM 1958). Jayne Cortez clearly demonstrates such qualities on her recording with bassist Richard Davis in Celebrations and Solitudes Strata East, 1974) and with her group the Firespitters on Taking The Blues Back Home ( Verve 1996), as did Gil Scott-Heron on "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised" and "B-Movie." And Kenneth Rexroth's Poetry and Jazz at the Blackhawk (Fantasy 1958) and Kenneth Patchen's Kenneth Patchen Reads with Jazz in Canada (Folkways 1959) clearly got it.

The Poetry of Jazz is at times angry, "They Feed They Lion" and "A Dozen Dawn Songs, Plus One." At others, it is tender and genuine without sentimentality as on "The Music of Time" and on the gorgeous "I Remember Clifford" with the sumptuous fluegelhorn of Tom Harrell (surely Clifford Brown's heir apparent on this planet) and les fils Boone (Asher and Atticus) providing additional brass support. The Poetry of Jazz has those same attributes in spades. Complementarity and congruence between the emotional tone of voice and music and their semantic content.

True there are fine guest performances to enjoy—Chris Potter on "The Unknowable (Homage to Sonny Rollins)," Greg Osby on "Call It Music (Homage to Charlie Parker," Branford Marsalis on "Soloing (Homage to John Coltrane)" and let's hear it again for Tom Harrell! But the stars here are Philip Levine's words and Benjamin Boone's totally assured and apposite compositions and arrangements. Indeed, some of these settings are achingly beautiful, such as "By the Waters of the Llobregat" with its simple, limpid piano accompaniment and the baroque-like "Our Valley." Poetry and jazz just grew up.

All About Jazz: How did you come to record The Poetry of Jazz with Phil Levine, America's poet laureate?

Benjamin Boone: "My writer friend, Danny Foltz-Gray, introduced me to Phil's work in the year 2000. I was applying for a faculty position at California State University Fresno and he said, "Fresno? My absolute favourite living poet teaches there, Philip Levine!" So, I checked out Phil's work and there was an immediacy and a relevance to it that spoke to me. It speaks of the working class, of toil and drudgery, genocide, race relations, and what work truly is. And when I listened to him read I could hear the musicality of his voice—his phrasing and rhythm and melodies. My doctoral dissertation had been a musical analysis of speech and I could certainly hear music in Phil's recitations.

"A little later, I was asked by a local film society to play at fundraiser where Phil was also asked to perform. I called him and we decided to collaborate. The reviews were stellar and people kept asking when we would perform again. So, we decided to see what would happen if we honed the pieces and recorded them. That experiment was a success, so over the next several years—almost right until his death—we recorded twenty-nine of his poems with music.

AAJ: The title of the album—The Poetry of Jazz—suggests that your aim was to bring about a correspondence between the sound of the voice/poetry and the music. How did you go about composing music that would match both Levine's lines and his remarkably compelling performance?

BB: "You are correct—creating a correspondence between the sound and meaning of the poetry and the sound and emotion of the music was our primary intent. The producer, Donald Brown, and the engineer, Mike Marciano, and I discussed this at great length—how to make it so that the voice was a member of the band. It didn't work at first by any means. I had to re-write all of the initial pieces we performed together on that first concert. It took time for us all to figure out each other's pacing and phrasing. But Phil caught on amazingly quickly.

"It was actually a fun process for me because I've studied words and the sounds of words since I was young. Because of some hearing issues I have that make it hard for me to understand words, I tend to focus on speech melody. Also, my older brother, Joseph A. Boone, is a literary scholar and both he and my mom read to me voraciously and instilled a love of language from an early age. Then in grad school, when I was composing art songs, operas, and musicals, I had to really think about the relationship between the vocalist and the musicians. So, I studied how great composers like Puccini approached the voice. I learned you have to leave sonic space for voice in the frequency spectrum and you have to be careful about what types of musical activity you do behind the voice without destroying the intelligibility of the words. So yes, I was really careful about when, where and how the voice was used."

AAJ: Often with music/spoken word projects, one feels that one or other suffers at the expense of the other, but that is not the case here. What were the practical issues involved for you and the group in the studio with Levine and how did you address these?

BB: "I'm delighted you feel a synergy between the words and the music and that they are equal partners. In fact, when I first knew I would be collaborating with Phil, I investigated several recordings of poets with musicians. I dug many of them, but to my musical ear, often the music was mostly reacting to the surface-level action of the poems—doing "word painting." In others, it sounded to me like the music was only an underscore to the reading. I know many people like many of these collaborations but it's not that interesting to me as a composer or a performer. So, I started thinking about how a classical composer might approach the voice.

"I decided early on that if I were to do this, my self-imposed challenge would be to find a way music could enhance the central meaning of each poem and have the music be an equal partner in communicating that emotion. The listener would have to experience the words in a different way than if it were a reading. Otherwise, what would be the point? One of my thoughts was that music can give the listener time to contemplate what they have heard—time for it sink beneath the surface—time for the listener to feel on a deeper level what is being expressed. This is especially true in poems like "By the Waters of the Llobregat," which is about genocide, or "What Work Is," which is about lost opportunities or "A Dozen Dawn Songs Plus One," which is about the horrid existence of workers. If the music doesn't enhance the poem and give it added value in some real, emotional way, and serve as an equal partner, then to me it's not as artistically interesting—at least for the duration of an entire CD.

"And, of course, there were issues about how we went about accurately capturing Phil's voice in the studio. Maximus Media Studio in Fresno, CA is well-known for its voice-over work. They really know how to record voice and that is a primary reason we recorded there. In the studio, Phil was in an isolation booth but with a giant window into the main room where the rest of the band was set up. His room was big and had wood floors and walls and that gave a warm natural reverb. Phil and I had spoken about the poems and how to read them, where to pause and so on. But we never rehearsed with the band. Instead, he asked that I indicate on the printout of his poems where he was to start, pause or resume and for how many seconds. Most of the time, I just gave him a visual cue—like a conductor. Phil was a huge jazz aficionado all of his life and part of what you are hearing is Phil's innate ability to hear and work with the band, as if he were a musician himself. His ability to hear when the piano fill was done or when the drum was cuing a new section or when the band was building or changing the feeling was incredible. He was intuitive and really got it. That is really the magic on these recordings. Take his reading of "Gin" -it's the first take. In fact, all are either first or second takes. Amazing."

AAJ: The subject matter of many of the poems here talk about jazz and musicians that Levine got to hear in person—"I Remember Clifford," "Unknowable" (an homage to Sonny Rollins), "Soloing" (a tribute to John Coltrane), "Call It Music" (about Charlie Parker's sad experiences in California but also remembering trumpeter Howard McGhee) and several others. Were these your choices or Phil Levine's and how far did you influence the selection of the poems to record?

BB: "Most were my choices but not all. I certainly wanted to record Phil's poems about the jazz legends you just mentioned—I mean, how cool is it that Phil knew Howard McGhee? Howard told him about Parker—and also his poems alluding to music in some way. But there were other poems that just spoke to me because when I read them I heard music. Or more accurately, when I heard Phil's voice in my head reading them, I heard melodies or how music could add to the overall emotional quality of the poetry. I am thinking of "Our Valley," which creates such a timeless sense a space when you read it. It begged for a music that captured this feeling of heat, space and expansive timelessness. It's also about the Valley in which I live, so I knew exactly what he was describing. "Gin" is just hysterically funny and poignant. I couldn't not do it.

"As the project progressed, Phil started suggesting poems as well, poems he hadn't read in public yet or ones that had not been collected. Before one of the later sessions he sent me this mail, saying, "Here is a long poem in sections, short ones. I've never even read it; it appeared somewhere about 2 years ago. It wants music." Attached was "A Dozen Dawn Songs, Plus One," which is really long, with the setting changing frequently.

"Now that presented a difficult compositional challenge. The poem is heavy to digest -"piss-speckled snow," Even the rats sense the perfume of things to come. At its core, it speaks of helplessness, oppression, and relentless hardship. How can that feeling be sustained over the entirety of this long poem and not turn the listener off? How can I create the feeling of being in an oppressive factory or a dingy sub-standard apartment or a shattered life?

"I was reminded of Ravel's Bolero, where one idea keeps intensifying for about fifteen minutes. I took this as my model and started with no pulse, then with a rhythmically complicated ostinato figure over which I then add industrial-type sounds. So at the beginning you hear a screech (a stick raked across a cymbal), then the low strings of a grand piano hit with the palm of a hand as the sustain pedal is depressed. The machine-like scratching sound at the beginning is a credit card being raked across dampened piano strings. Listen and you can hear that the groove never really changes—it is relentless throughout, like in Bolero, and the melody doesn't arrive until near the end. It was an experiment in using limited musical material and stretching it for a long time. I am hoping Ravel would have been proud.

AAJ: It is hard to pick out a standout track but "Yakov," a lovely tale of friendship and loss, "They Feed They Lion," the high drama of "The Waters of the Llobregat" and "I Remember Clifford" represent quite special achievements. Yet each track is very different.

BB: "I appreciate that. I like these settings, too. "Yakov" is indeed about friendship and loss but also about how we view immigrants in this country and is really relevant today. That's one of the reasons I wanted to set this poem. In fact, we have recorded an instrumental version of "Yakov" that will appear on Volume II, which will be out in January 2019. We also have an instrumental coming out on Volume II of "They Feed They Lion."

"They Feed They Lion" is my writer friend's favourite Levine poem. He suggested I set it. It's about a race riot that happened in Detroit but it could be about any of the horrid racist events in the USA going on even now. Phil said he wanted to record this with a much different tone than he had used in the past. This was about the time the Black Lives Matter movement was starting. He wanted it to be angrier than prior readings and to sound almost like a preacher.

"Phil gave only small bits of guidance about the setting of his poems. He said the music for "Unholy Saturday" was too slow. So, we didn't record it. He asked whether I really wanted to record a poem as long as "Call It Music." I did. He also didn't like a guitar part, which we then cut out. But he did give clear direction—probably more than for any other poem—for "They Feed They Lion." In an email of August 13, 2012 he wrote:

"I've been thinking about how best to do "They Lion." I settled on a strategy of going in the opposite direction from what's been done in the past. Let the poem be . . . what?. . . violent? attacking? brutal?... & the music fairly calm until the pause before the storm of the final stanza. And then the horn continues into the final stanza—that would be the only time the horn & the poem are heard together. Have a break after each stanza of say half a minute or less, a break without fireworks but with mounting intensity, & then GO! In the breaks between stanzas, the horn answers the reading voice of the previous stanza."

"So, I changed the arrangement I had made, cutting out a contrasting section and saving the melody for the final climax. We recorded this at the very end of the session and Phil's voice was tired. He almost didn't record it. He was exhausted, not feeling well, and had said it was time for him to go home. But then he looked at the list of the tracks and saw "They Feed They Lion" was next and decided to stay and record it. That took tremendous energy. What you hear is his passion and vigour.

""The Water of the Llobregat" is such a heavy poem. How do you write music for a poem about genocide? I decided that the listener needed the time and space to process the depth of the words, to let them sink in deep. So, I used lots of space—long sustains in the piano, lots of time between phrases, spread out and uncluttered chords, flexing the tempo, until near the end when it becomes dissonant and relentless. We hoped each piece would create a unique sound world in which the poem could reside.

AAJ: The Poetry of Jazz features several guest performances—Chris Potter on "Unknowable," Branford Marsalis on "Soloing," Greg Osby on "Call It Music" and, perhaps best of all, the wonderful Tom Harrell on "I Remember Clifford." What is it about these particular musicians that made you choose them for these particular tracks?

BB: "I recall listening to what I thought was the final version of "I Remember Clifford" about trumpet legend Clifford Brown. I heard myself playing the melody on saxophone, and I thought, 'It's just wrong for me, a saxophonist, to be taking the lead on this track.' So, my producer-extraordinaire Donald Brown got Tom Harrell, who was deeply influenced by Brown, to do it.

"That logic extended to Chris Potter, who gets the big sound of Sonny Rollins, replacing my playing on "The Unknowable" about Rollins' hiatus from the public eye. Greg Osby, who sounds like what Charlie Parker would have sounded like had he lived longer, replaced me on "Call It Music," a poem that recounts a story related to Levine by his teacher, Howard McGhee, the trumpeter at the famed Dial recording session of "Lover Man," where Parker was intoxicated. And lastly, Branford Marsalis, who I knew through a connection with the New Century Saxophone Quartet's Steve Pollock, recorded "Soloing," in which Levine compares his aging mother's isolated existence to a Coltrane solo.

"It was tempting to have these jazz greats play on more than one track, but that would have defeated my primary reason for having them, namely to make the "homage" tracks special. I used a number of other musicians to help each track sound unique, like pianist, Craig von Berg, who you can hear adding crazy piano sounds to "A Dozen Dawn Songs Plus One." German violinist, Stefan Poetzsch, contributes to both "Dawn Songs" and "Our Valley," while Karen Marguth added vocalizations to "Gin" and "Music of Time." My two sons, Atticus and Asher Boone, joined me to form the backup 'horn section' on "I Remember Clifford." and trumpeter Max Hembd added harmony parts on several tracks."

AAJ: What is it for you that makes Phil Levine's performances here quite so powerful, so transcendent?

BB: "Well, I think it's pretty simple. Phil's voicing, timing, inflection, articulations, tempo, dynamics and just his ability to jam with the band was unparalleled. That allows the listener to hear and feel his poignant, powerful, easy to grasp and immediate poetry. The listener gets the point and it is deep, while the music grants them the time to process it and helps guide the poetic narrative. The topics are as relevant today as they were when he wrote them. Sadly, my guess is they will always be. Phil's words speak of truths inside all human beings—universal feelings we often repress or tamp down or simply don't recognize. His poetry allows us to let them in, to feel them and to see beyond ourselves. It's timeless and, as you say, transcendent."

Soundclips

Other Reviews of

"The Poetry of Jazz":

JazzDaGama by Raul da Gama

The Jazz Duck by Editor

JazzTimes by Britt Robson

Step Tempest by Richard Kamins

The Normal School Literary Magazine by Optimism One

Downbeat by Michael Jackson

Jazz Weekly by George W. Harris

The Aquarian by Mike Greenblatt

Improvijazzation Nation by Rotcod Zzaj

New York City Jazz Record by John Pietaro

The Paris Review by Jeffery Gleaves

JazzTimes by Andrew Gilbert

NPR - All Things Considered by Tom Vitale

All About Jazz by Mark Corroto

Fresno Bee by Joshua Tehee