MUSIC REVIEW BY Harvey Siders, JazzTimes

No matter what Thomas Wolfe predicted: you can go home again.

Saxophonist Don Lanphere managed to get back there. From "the apple" to the Apple, and a final return to "the apple"-"the apple" being rural Wenatchee, aka "the apple capital of Washington." The moves correspond with the parameters of Lanphere's career: from a promising jazz launch in the 1950s, through a higher trajectory into the self-destructive orbit of bebop, to a safe, born-again landing in 1969, where the terra has never been more firma.

"At 73, I'm having more fun playing and playing better than I ever did," claims Lanphere in the home studio of his Kirkland, Wash., residence, a room cluttered with priceless photographs, music, albums and precious memorabilia. "I spoke to Phil Woods a few days ago, a few days after his 70th birthday, and he told me the same thing."

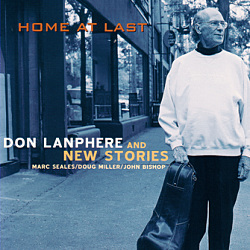

Listening to his latest CD, Home at Last (Origin-82391), I couldn't disagree with either boast. Despite his thin frame, Lanphere looks his age but he certainly doesn't act it; his movements are occasionally unsteady, but his focus is always firm; his trademark ponytail and the equally famous seaman's cap from which it emerged no longer exist, leaving an honest but bald pate. His hands are remarkably young looking with long fingers that any pianist would envy. Add to the mix his gentle sense of humor and that slightly crooked laugh, and you find yourself warmed by his cool.

As evidenced by Home at Last, the fluidity of his technique, the clarity of his tone and the logic of his improvisational ideas have never abandoned him. Playing better? To say he's playing as well as he ever did could not be surpassed as a compliment. He lists the usual suspects among his early influences: Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Dexter Gordon, Sonny Stitt and a bit later, more significantly, Charlie Parker. They're all still ingredients in his bop bouillabaisse, but to my ears, Dexter and Lester are the ones who leave the most flavorful aftertaste, and tend to shape how Lanphere approaches up-tunes and ballads, respectively.

Donald Gale Lanphere was born in Wenatchee June 26,1928. At age seven he discovered his dad's well-hidden tenor sax and "got caught" trying to coax sounds from it. Fortunately his father understood Lanphere's desire for some kind of musical outlet, having enjoyed a brief career of his own, playing in ballrooms throughout California.

So the lessons began and his musical instincts quickly took over from there. When he was 14, he formed a quartet and tried to play in the cocktail lounge of the local Elks Lodge. "Of course the only way that could happen was under parental supervision, so my dad played bass so I could play there." In his senior year in high school in Wenatchee, he transcribed Coleman Hawkins' "Body and Soul" note for note and quickly made good use of it. "When I was 17, the first summer I came home from Northwestern University, near Chicago, Jimmie Lunceford's band played in Wenatchee and somebody there told him, 'There's a young sax player in town who plays pretty good and he's here tonight.' Lunceford said, 'Oh really? Bring him up.' So I came up and he said, 'Whaddya wanna play?' And I said 'Body and Soul.' I could see some eyebrows rising, but I played the entire Hawkins transcription and then I saw guys like Willie Smith, Joe Thomas and Trummy Young looking at each other and nodding. Years later I was playing in Honolulu with Trummy and when I told him that story he said, 'You were that kid?'"

Back at Northwestern, that same kid passed musical puberty, playing at all-night sessions with Jimmy Raney and Junior Mance ("Back then, he was called Julian") and that's when his tastes began to change. "I was still in the Coleman Hawkins stage, and these guys would say, 'How come you play like that? Haven't you heard what Charlie Parker is doing, or that new kid out in L.A., Dexter Gordon? No? Man you got a lot of learning to do.' So they took me under their wing and by the time I got to 'Now's the Time' and 'Billie's Bounce' my head was turned in a completely different direction and I've never looked back."

Stylistically he never had to look back, but he has such a wealth of memories-both precious and regrettable-that talking with Lanphere is tantamount to collecting an oral history of the most exciting, innovative and self-destructive eras in jazz history. "One of the first things that comes to mind is my high-school band director. When I was ready to make the move to college, he told me, 'When you come home for Christmas, bring some of that good Chicago green.' I said, 'What's that?' and he said, 'Oh you'll find it-just ask.' I found it easily enough. It was a very high grade of marijuana, and by the time I brought back some for him, I had tried it and that was the start of 22 years of addiction."

Lanphere quickly landed a job playing with Johnny Bothwell's sextet, graduated from pot to heroin, but never graduated from Northwestern. When Bothwell suddenly decided to conquer New York, Lanphere dropped out of college and found himself in the Big Apple, "playing at the Baby Grand, on 125th Street, just three doors down from the Apollo. It's still there."

On opening night, Bothwell brought his date to the club, Chan Richardson. The fiercely independent Richardson decided to leave with Lanphere. "She decided to go for the new kid on the block. I was only 20, but she took me home with her. Bothwell fired me the next night, but the owner of the Baby Grand wanted the group to remain intact and forced Bothwell to keep me on for two weeks."

Lanphere and Richardson remained together in a common-law marriage for two years (she showed an obvious predilection for bop-oriented saxophonists by moving on to marry Charlie Parker and, later, Phil Woods) and she played a significant role for jump-starting his career. She coaxed Dial Records owner Ross Russell to listen to Lanphere, and that led swiftly to a 1948 session with Fats Navarro and Max Roach, who were backing singer Earl Coleman. Of course, Lanphere had to prove that he could keep up with these future giants of bop, and as Lanphere recalls, "It was trial by fire and I survived; they started taking me around to various clubs." That led eventually to playing with the bona fide boss of bop, Charlie Parker.

It also led to even deeper addiction, the so-called "suicide room," the apartment on 52nd Street where Lanphere and Richardson lived, the place where all the hip players on the street spent their breaks. Even in his drug and alcohol-induced haze, Lanphere knew he had to get out of that environment. If he needed proof, it came when he had to be bailed out of jail by his parents in 1951 when he was busted for possession. He returned home for a while to the relative security of Wenatchee and the music store his dad operated there.

Enter Midge Hess, who walked into the store one day in 1952, looking for a particular music magazine. Lanphere took one look, liked what he saw, walked her home and the following year they were married. She didn't know too much about music, but that didn't stop her from offering this timeless advice: "Doodle, doodle, doodle-is that all you do? Why don't you just play me a pretty melody like Stan or Zoot?" He immortalized her with two lovely, rhapsodic, appropriately named ballad collections for the Scottish HEP label: Don Loves Midge in 1993 and, four years later, Don Still Loves Midge.

Midge proved to be a stabilizing factor in Don's life, even though she had LSD-related problems of her own. They traveled together for many years, while Lanphere improved the quality of his musical environment, playing with Artie Shaw, Charlie Barnet, Claude Thornhill and a number of Woody Herman's Herds. By '61, with his personal demons still not exorcized, Lanphere opted for Wenatchee and the music store again, but it amounted to virtually disappearing from the jazz radarscope-seldom traveling, on the verge of becoming a rarely heard legend-until the pivotal year of 1969.

"I remember this so clearly. A group had come through Wenatchee to play at the Bright Moon Tavern-they had been at the store earlier that day to buy some extra guitar strings-so I went down there a little too late and noticed the crowd coming out shaking their heads, so I asked what happened. They told me, 'There was a young band in there, singing about Jesus. And everyone put down their drinks and cigarettes and just listened. It was very touching.' I tried to catch up to them at Denny's where they went after the gig and I met a pastor from Wenatchee, a pastor from Seattle, and a fellow they called Brother Bud who was a reformed drug addict. We sat down at a booth, held hands and Brother Bud took me to the Lord."

In the account he gave Dr. Dan Tripps for his book The Heart of Success (BainBridgeBooks), Lanphere amplified that unforgettable moment, saying, "I found myself repeating what he asked me to, 'Lord Jesus come into my heart.'" Lanphere got up from the booth-and fell right to the floor. When Lanphere got home he told Midge he had been saved. (Long before she met Don, Midge had reportedly been saved by a then-obscure minister named Billy Graham.) But this was a magical moment and, as Tripps writes, "on Nov. 5, 1969, they both flushed their reds, and yellows and grass down the toilet." They've never gone back to their old ways.

After his parents died, Lanphere sold the store, and with Midge's encouragement, moved to Seattle to see if his career could also be reborn.

Slowly he tested the waters, filling in for Getz at one gig, touring with Maynard Ferguson in British Columbia, playing a gig at Manhattan's West End Café, studiously avoiding the old haunts. There was a lot of fear, he says, "but as soon as the music starts, the passion takes over the fear." For the past 13 years, Lanphere has been on the faculty of the Port Townsend Jazz Festival, thanks to Bud Shank. And his recording activities are alive and well, thanks to a close-knit, highly supportive rhythm section known as New Stories (pianist Marc Seales, bassist Doug Miller, drummer John Bishop). They've put out a series of recordings on the Origin label, the latest of which brings us full circle to Home at Last.

Home has taken on an entirely new meaning for Don Lanphere. For the past three years he and Midge have lived in Kirkland, which is due east of Seattle on the other side of Lake Washington. Their place is on a quiet residential street about three blocks from the lake. Lanphere has 30 students, including some high-schoolers, a lot of college students, even his own cardiologist. "One of the reasons I'm playing so well these days is because of those students. They're all at different levels, and what's so intriguing are the college hot shots who come here to shoot the old man down."

But they can't shoot the old man down; he's got a higher power on his side. He's very active in his local Foursquare church, occasionally playing concerts there and at other churches. He also frequently tours Christian universities, lecturing to the students and holding clinics for their jazz bands. Lanphere also has three Christian jazz CDs in circulation on the DGL label. (Not surprisingly, the letters stand for Donald Gale Lanphere.) Finally, he prays every day. If he knows you have some affliction he'll pray for you, but, not being pushy, he'll first ask your permission. As Michael Zwerin recounted in the N.Y. Herald Tribune a couple of years ago, "A piano player he knows who had a serious hand problem [said] 'Yes, man, I do mind. I don't want your prayers.'" Lanphere pointed out "When I'm away from him I do it anyway...one thing people can't do is stop you from praying for them."

Playing or praying, secular or sacred, it's good to have the survivor completely home at last.

Listening Pleasures

His current list includes: Michel Legrand's Legrand Jazz; Herbie Hancock's Gershwin's World; Frank Sinatra's In the Wee Small Hours; Miles Davis' Ballads; Don Still Loves Midge; Joe Henderson's So Near, So Far; Shirley Horn's You're My Thrill and Gene Roland's collection The Band That Never Was. For the desert island, "anything by Bird."

On his classical list: Barber's "Adagio for Strings," Schoenberg's "Transfigured Night," the two piano concertos by Ravel, Debussy's "La Mer," Holst's "The Planets," Shostakovich's "Fifth Symphony," Stravinsky's "The Firebird" and David Diamond's "Symphony no. 3." For that fabled desert island (hope there's a Bose available): the two "Daphnis and Chloe" suites by Ravel.

Gearbox

"I have a new plaything here, put out by SuperScope/Marantz Professional. Officially it's called SuperScope Compact Disc Digital Audio CD-RW Playback. All I know is it enables me to take any tune and slow it down as far as half speed, or take it up to double time and not change the pitch. Consequently, a line that's really bothering me-and sometimes it's one I wrote myself, sometimes so difficult that Jonathan Pugh, my cornet player, can't play it. But with this thing, I can and he can. Another feature is the 'A-B Loop': it lets me repeat certain lines over and over again, for the rest of my life, if necessary. Indispensable for transcribing.

Lanphere also luxuriates in his Bose radio, with CD player. Its "audio wavelength" really fills his studio.

As for horns, "I started out with Selmer tenors and altos, then switched to King Super 20, but for the past 15 years I've played soprano, alto and tenor saxes made by Yanagisawa exclusively. That's a company that began in Japan around 1890 and all they make are saxes, from the sopranino down to the big bass sax. As for reeds, I use only Fibracell."

https://jazztimes.com/archives/don-lanphere/

Saxophonist Don Lanphere managed to get back there. From "the apple" to the Apple, and a final return to "the apple"-"the apple" being rural Wenatchee, aka "the apple capital of Washington." The moves correspond with the parameters of Lanphere's career: from a promising jazz launch in the 1950s, through a higher trajectory into the self-destructive orbit of bebop, to a safe, born-again landing in 1969, where the terra has never been more firma.

"At 73, I'm having more fun playing and playing better than I ever did," claims Lanphere in the home studio of his Kirkland, Wash., residence, a room cluttered with priceless photographs, music, albums and precious memorabilia. "I spoke to Phil Woods a few days ago, a few days after his 70th birthday, and he told me the same thing."

Listening to his latest CD, Home at Last (Origin-82391), I couldn't disagree with either boast. Despite his thin frame, Lanphere looks his age but he certainly doesn't act it; his movements are occasionally unsteady, but his focus is always firm; his trademark ponytail and the equally famous seaman's cap from which it emerged no longer exist, leaving an honest but bald pate. His hands are remarkably young looking with long fingers that any pianist would envy. Add to the mix his gentle sense of humor and that slightly crooked laugh, and you find yourself warmed by his cool.

As evidenced by Home at Last, the fluidity of his technique, the clarity of his tone and the logic of his improvisational ideas have never abandoned him. Playing better? To say he's playing as well as he ever did could not be surpassed as a compliment. He lists the usual suspects among his early influences: Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Dexter Gordon, Sonny Stitt and a bit later, more significantly, Charlie Parker. They're all still ingredients in his bop bouillabaisse, but to my ears, Dexter and Lester are the ones who leave the most flavorful aftertaste, and tend to shape how Lanphere approaches up-tunes and ballads, respectively.

Donald Gale Lanphere was born in Wenatchee June 26,1928. At age seven he discovered his dad's well-hidden tenor sax and "got caught" trying to coax sounds from it. Fortunately his father understood Lanphere's desire for some kind of musical outlet, having enjoyed a brief career of his own, playing in ballrooms throughout California.

So the lessons began and his musical instincts quickly took over from there. When he was 14, he formed a quartet and tried to play in the cocktail lounge of the local Elks Lodge. "Of course the only way that could happen was under parental supervision, so my dad played bass so I could play there." In his senior year in high school in Wenatchee, he transcribed Coleman Hawkins' "Body and Soul" note for note and quickly made good use of it. "When I was 17, the first summer I came home from Northwestern University, near Chicago, Jimmie Lunceford's band played in Wenatchee and somebody there told him, 'There's a young sax player in town who plays pretty good and he's here tonight.' Lunceford said, 'Oh really? Bring him up.' So I came up and he said, 'Whaddya wanna play?' And I said 'Body and Soul.' I could see some eyebrows rising, but I played the entire Hawkins transcription and then I saw guys like Willie Smith, Joe Thomas and Trummy Young looking at each other and nodding. Years later I was playing in Honolulu with Trummy and when I told him that story he said, 'You were that kid?'"

Back at Northwestern, that same kid passed musical puberty, playing at all-night sessions with Jimmy Raney and Junior Mance ("Back then, he was called Julian") and that's when his tastes began to change. "I was still in the Coleman Hawkins stage, and these guys would say, 'How come you play like that? Haven't you heard what Charlie Parker is doing, or that new kid out in L.A., Dexter Gordon? No? Man you got a lot of learning to do.' So they took me under their wing and by the time I got to 'Now's the Time' and 'Billie's Bounce' my head was turned in a completely different direction and I've never looked back."

Stylistically he never had to look back, but he has such a wealth of memories-both precious and regrettable-that talking with Lanphere is tantamount to collecting an oral history of the most exciting, innovative and self-destructive eras in jazz history. "One of the first things that comes to mind is my high-school band director. When I was ready to make the move to college, he told me, 'When you come home for Christmas, bring some of that good Chicago green.' I said, 'What's that?' and he said, 'Oh you'll find it-just ask.' I found it easily enough. It was a very high grade of marijuana, and by the time I brought back some for him, I had tried it and that was the start of 22 years of addiction."

Lanphere quickly landed a job playing with Johnny Bothwell's sextet, graduated from pot to heroin, but never graduated from Northwestern. When Bothwell suddenly decided to conquer New York, Lanphere dropped out of college and found himself in the Big Apple, "playing at the Baby Grand, on 125th Street, just three doors down from the Apollo. It's still there."

On opening night, Bothwell brought his date to the club, Chan Richardson. The fiercely independent Richardson decided to leave with Lanphere. "She decided to go for the new kid on the block. I was only 20, but she took me home with her. Bothwell fired me the next night, but the owner of the Baby Grand wanted the group to remain intact and forced Bothwell to keep me on for two weeks."

Lanphere and Richardson remained together in a common-law marriage for two years (she showed an obvious predilection for bop-oriented saxophonists by moving on to marry Charlie Parker and, later, Phil Woods) and she played a significant role for jump-starting his career. She coaxed Dial Records owner Ross Russell to listen to Lanphere, and that led swiftly to a 1948 session with Fats Navarro and Max Roach, who were backing singer Earl Coleman. Of course, Lanphere had to prove that he could keep up with these future giants of bop, and as Lanphere recalls, "It was trial by fire and I survived; they started taking me around to various clubs." That led eventually to playing with the bona fide boss of bop, Charlie Parker.

It also led to even deeper addiction, the so-called "suicide room," the apartment on 52nd Street where Lanphere and Richardson lived, the place where all the hip players on the street spent their breaks. Even in his drug and alcohol-induced haze, Lanphere knew he had to get out of that environment. If he needed proof, it came when he had to be bailed out of jail by his parents in 1951 when he was busted for possession. He returned home for a while to the relative security of Wenatchee and the music store his dad operated there.

Enter Midge Hess, who walked into the store one day in 1952, looking for a particular music magazine. Lanphere took one look, liked what he saw, walked her home and the following year they were married. She didn't know too much about music, but that didn't stop her from offering this timeless advice: "Doodle, doodle, doodle-is that all you do? Why don't you just play me a pretty melody like Stan or Zoot?" He immortalized her with two lovely, rhapsodic, appropriately named ballad collections for the Scottish HEP label: Don Loves Midge in 1993 and, four years later, Don Still Loves Midge.

Midge proved to be a stabilizing factor in Don's life, even though she had LSD-related problems of her own. They traveled together for many years, while Lanphere improved the quality of his musical environment, playing with Artie Shaw, Charlie Barnet, Claude Thornhill and a number of Woody Herman's Herds. By '61, with his personal demons still not exorcized, Lanphere opted for Wenatchee and the music store again, but it amounted to virtually disappearing from the jazz radarscope-seldom traveling, on the verge of becoming a rarely heard legend-until the pivotal year of 1969.

"I remember this so clearly. A group had come through Wenatchee to play at the Bright Moon Tavern-they had been at the store earlier that day to buy some extra guitar strings-so I went down there a little too late and noticed the crowd coming out shaking their heads, so I asked what happened. They told me, 'There was a young band in there, singing about Jesus. And everyone put down their drinks and cigarettes and just listened. It was very touching.' I tried to catch up to them at Denny's where they went after the gig and I met a pastor from Wenatchee, a pastor from Seattle, and a fellow they called Brother Bud who was a reformed drug addict. We sat down at a booth, held hands and Brother Bud took me to the Lord."

In the account he gave Dr. Dan Tripps for his book The Heart of Success (BainBridgeBooks), Lanphere amplified that unforgettable moment, saying, "I found myself repeating what he asked me to, 'Lord Jesus come into my heart.'" Lanphere got up from the booth-and fell right to the floor. When Lanphere got home he told Midge he had been saved. (Long before she met Don, Midge had reportedly been saved by a then-obscure minister named Billy Graham.) But this was a magical moment and, as Tripps writes, "on Nov. 5, 1969, they both flushed their reds, and yellows and grass down the toilet." They've never gone back to their old ways.

After his parents died, Lanphere sold the store, and with Midge's encouragement, moved to Seattle to see if his career could also be reborn.

Slowly he tested the waters, filling in for Getz at one gig, touring with Maynard Ferguson in British Columbia, playing a gig at Manhattan's West End Café, studiously avoiding the old haunts. There was a lot of fear, he says, "but as soon as the music starts, the passion takes over the fear." For the past 13 years, Lanphere has been on the faculty of the Port Townsend Jazz Festival, thanks to Bud Shank. And his recording activities are alive and well, thanks to a close-knit, highly supportive rhythm section known as New Stories (pianist Marc Seales, bassist Doug Miller, drummer John Bishop). They've put out a series of recordings on the Origin label, the latest of which brings us full circle to Home at Last.

Home has taken on an entirely new meaning for Don Lanphere. For the past three years he and Midge have lived in Kirkland, which is due east of Seattle on the other side of Lake Washington. Their place is on a quiet residential street about three blocks from the lake. Lanphere has 30 students, including some high-schoolers, a lot of college students, even his own cardiologist. "One of the reasons I'm playing so well these days is because of those students. They're all at different levels, and what's so intriguing are the college hot shots who come here to shoot the old man down."

But they can't shoot the old man down; he's got a higher power on his side. He's very active in his local Foursquare church, occasionally playing concerts there and at other churches. He also frequently tours Christian universities, lecturing to the students and holding clinics for their jazz bands. Lanphere also has three Christian jazz CDs in circulation on the DGL label. (Not surprisingly, the letters stand for Donald Gale Lanphere.) Finally, he prays every day. If he knows you have some affliction he'll pray for you, but, not being pushy, he'll first ask your permission. As Michael Zwerin recounted in the N.Y. Herald Tribune a couple of years ago, "A piano player he knows who had a serious hand problem [said] 'Yes, man, I do mind. I don't want your prayers.'" Lanphere pointed out "When I'm away from him I do it anyway...one thing people can't do is stop you from praying for them."

Playing or praying, secular or sacred, it's good to have the survivor completely home at last.

Listening Pleasures

His current list includes: Michel Legrand's Legrand Jazz; Herbie Hancock's Gershwin's World; Frank Sinatra's In the Wee Small Hours; Miles Davis' Ballads; Don Still Loves Midge; Joe Henderson's So Near, So Far; Shirley Horn's You're My Thrill and Gene Roland's collection The Band That Never Was. For the desert island, "anything by Bird."

On his classical list: Barber's "Adagio for Strings," Schoenberg's "Transfigured Night," the two piano concertos by Ravel, Debussy's "La Mer," Holst's "The Planets," Shostakovich's "Fifth Symphony," Stravinsky's "The Firebird" and David Diamond's "Symphony no. 3." For that fabled desert island (hope there's a Bose available): the two "Daphnis and Chloe" suites by Ravel.

Gearbox

"I have a new plaything here, put out by SuperScope/Marantz Professional. Officially it's called SuperScope Compact Disc Digital Audio CD-RW Playback. All I know is it enables me to take any tune and slow it down as far as half speed, or take it up to double time and not change the pitch. Consequently, a line that's really bothering me-and sometimes it's one I wrote myself, sometimes so difficult that Jonathan Pugh, my cornet player, can't play it. But with this thing, I can and he can. Another feature is the 'A-B Loop': it lets me repeat certain lines over and over again, for the rest of my life, if necessary. Indispensable for transcribing.

Lanphere also luxuriates in his Bose radio, with CD player. Its "audio wavelength" really fills his studio.

As for horns, "I started out with Selmer tenors and altos, then switched to King Super 20, but for the past 15 years I've played soprano, alto and tenor saxes made by Yanagisawa exclusively. That's a company that began in Japan around 1890 and all they make are saxes, from the sopranino down to the big bass sax. As for reeds, I use only Fibracell."

https://jazztimes.com/archives/don-lanphere/

Soundclips

Other Reviews of

"Home At Last":

amazon.com by amazon.com

Berman Music Review by Butch Berman

All About Jazz by Joseph Blake

JazzTimes 2001 by Ira Gitler

Earshot Magazine, January 2002 by Peter Monaghan

All Music Guide by Dave Nathan

Muses Muse by Ben Ohmart