MUSIC REVIEW BY Howard Reich, Chicago Tribune

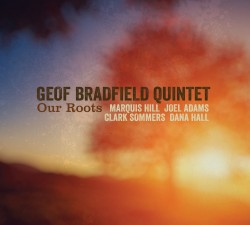

Chicago saxophonist Geof Bradfield long has been drawn to the music of Lead Belly, and a while ago he got to do something about it. Invited by impresario Chris Anderson to pick a favorite album and perform its music at the Fulton Street Collective, Bradfield chose saxophonist Clifford Jordan's homage to Lead Belly, "These Are My Roots." But Bradfield felt free to reimagine the work according to his own tastes, the venture inspiring him to document his thoughts on Lead Belly's songs in particular, Southern blues/folk in general, via the new recording "Our Roots" (Origin Records). To celebrate its release, Bradfield convened the powerhouse quintet from that album Friday night at the Green Mill Jazz Club, kicking off a weekend's worth of shows. The result was not so much a restatement of Lead Belly's aesthetic as rigorous jazz improvisation inspired by it.

For starters, Bradfield was joined by several Chicago jazz musicians of comparable focus and intensity. True, trumpeter Marquis Hill moved to New York last year, shortly before winning the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Trumpet Competition, but he has been playing Chicago's clubs and concert halls with such regularity that he hardly seems to have left. Add to Hill's vigorous solos drummer Dana Hall's characteristically volatile work, Clark Sommers' warmly stated bass playing and Joel Adams' rambunctious trombone cadenzas, and you had a quintet bound to make an impression regardless of the repertoire at hand.

In the music of Lead Belly and other traditional fare, Bradfield and friends captured the melodic urgency of age-old songs but built complex jazz structures upon them. Bradfield states in the liner notes for "Our Roots" that he considers much of this music "simple and direct," which it is - at its core. But neither Bradfield nor his colleagues hesitated to play intricate solos or cleverly voiced ensemble passages that took Lead Belly's music into distant realms.

Some of the most searing sounds of the evening's first set unfolded in "Dick's Holler," the performance opening with what amounted to a lament for three horns. To hear Bradfield's imploring phrases on tenor saxophone, Hill's nimble lines on trumpet and Adams' burnished tone on trombone was to savor three-part counterpoint steeped in blues expression. But that was just the curtain-raiser for solos of considerable detail, the musicians' straightforward blues lines intertwined with gnarly jazz transformations of them.

Bradfield turned in his best work in "Black Girl," paring the band down to a trio for his most extended solo of the set. Backed only by drummer Hall and bassist Sommers, the saxophonist offered an extended essay in which one theme flowed into another, the saxophonist building an argument through both exacting technique and oratorical flourish.

When the quintet reunited for "Black Betty," trumpeter Hill produced a solo of piercing lyricism before all the horns joined forces for a rhythmically surging thematic recap. This was music of inherent drama and force, dispatched by a quintet that showed increasing cohesion as the evening progressed.

To Bradfield and friends, Lead Belly's rough-and-ready music stands as a gateway to ornate jazz improvisation, and they made the most of it.

For starters, Bradfield was joined by several Chicago jazz musicians of comparable focus and intensity. True, trumpeter Marquis Hill moved to New York last year, shortly before winning the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Trumpet Competition, but he has been playing Chicago's clubs and concert halls with such regularity that he hardly seems to have left. Add to Hill's vigorous solos drummer Dana Hall's characteristically volatile work, Clark Sommers' warmly stated bass playing and Joel Adams' rambunctious trombone cadenzas, and you had a quintet bound to make an impression regardless of the repertoire at hand.

In the music of Lead Belly and other traditional fare, Bradfield and friends captured the melodic urgency of age-old songs but built complex jazz structures upon them. Bradfield states in the liner notes for "Our Roots" that he considers much of this music "simple and direct," which it is - at its core. But neither Bradfield nor his colleagues hesitated to play intricate solos or cleverly voiced ensemble passages that took Lead Belly's music into distant realms.

Some of the most searing sounds of the evening's first set unfolded in "Dick's Holler," the performance opening with what amounted to a lament for three horns. To hear Bradfield's imploring phrases on tenor saxophone, Hill's nimble lines on trumpet and Adams' burnished tone on trombone was to savor three-part counterpoint steeped in blues expression. But that was just the curtain-raiser for solos of considerable detail, the musicians' straightforward blues lines intertwined with gnarly jazz transformations of them.

Bradfield turned in his best work in "Black Girl," paring the band down to a trio for his most extended solo of the set. Backed only by drummer Hall and bassist Sommers, the saxophonist offered an extended essay in which one theme flowed into another, the saxophonist building an argument through both exacting technique and oratorical flourish.

When the quintet reunited for "Black Betty," trumpeter Hill produced a solo of piercing lyricism before all the horns joined forces for a rhythmically surging thematic recap. This was music of inherent drama and force, dispatched by a quintet that showed increasing cohesion as the evening progressed.

To Bradfield and friends, Lead Belly's rough-and-ready music stands as a gateway to ornate jazz improvisation, and they made the most of it.

Soundclips

Other Reviews of

"Our Roots":

JAZZIZ by Bob Weinberg

Downbeat by Michael Jackson

Jazz History Online by Thomas Cunniffe

Bird is the Worm by Dave Sumner

WTJU - Richmond by Dave Rogers

South Bend Tribune by Howard Dukes

Chicago Reader by Peter Margasak

Downbeat by Peter Margasak

Downbeat by Brian Zimmerman

KUCI, Irvine, CA by Hobart Taylor

Midwest Record by Chris Spector

All About Jazz by Mark Corroto

All About Jazz by Dan McClenaghan