MUSIC REVIEW BY Josef Woodard, DownBeat Magazine

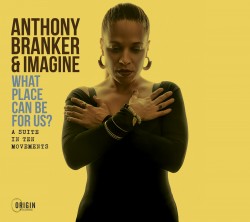

WHILE THE TRAJECTORY OF A JAZZ MUSICIAN'S career often follows a somewhat logical arc, others take more complex and evolving paths. The latter has been the fate — mostly self-designed — of Dr. Anthony Branker, whose latest album is one of his most ambitious projects. What Place Can Be For Us? A Suite In Ten Movements is a sweeping opus with sociopolitical and poetic content woven into a musical tapestry — with his band Imagine — which manages to be at once cerebral, emotive and viscerally exciting.

The project, Branker's eighth album for Origin Records, is imbued with the wisdom earned and musical lessons learned in his life as a veteran educator (currently at Rutgers, after retiring from Princeton), as a respected conductor for music by Wynton Marsalis, Terence Blanchard and Duke Ellington, and a composer/conceptualist. His powers in and commitment to that role grew dramatically after catastrophic health issues more-or-less ended his life as a trumpeter in 1999. The long, dedicated road has led Branker to this point, and he professes to be as creatively engaged and forward-thinking as ever. At 65, he asserts, "I feel as though I am just beginning to come into my own as a composer, so I just want to keep writing, learning, growing and sharing."

As for the story, or matrix of stories, told in his new suite, Branker explains that "the actual commitment to write this suite came after a period of seeing some incredibly disturbing images on television of the horrific suffering the citizens of Syria were experiencing during the country's ongoing civil war. This was when many were seeking refuge in a number of countries. Interestingly, though, I had been thinking about a number of issues associated with the concept of 'place,' such as what does place mean or represent, and how it is a universal concept that all of us can relate to on some level. "With all of this swirling around in my mind, I was driven to develop this extended work, which would allow me to offer my own creative responses to a number of historical and social occurrences. I could begin to unpack such overarching issues as inclusion and belonging while also addressing what I have described as circumstances of exploitation and zones of refuge experienced by people of color and other global citizens."

As Branker says, working in the broader canvas and modular strategy of creating a suite, versus discrete "tunes," has been an awakening process for him as a composer. He recalls the influence of a BMI Jazz Composers Workshop in the early 1990s, with innovative big band leaders Jim McNeely and Manny Albam, and McNeely's narrative vison of writing "with characters and episodes unfolding and developing time as part of the flow of a piece. It has been an eye-opening experience to embrace this kind of organizational thinking because I can approach the writing process in a more open, organic and episodic way. I could now start to consider things more like a visual artist would or a filmmaker who is imagining flow in more cinematic terms."

Fittingly, the suite's journey opens with "Door Of No Return," a reference to a slave trade shipping "place" in Senegal, with vocalist Alison Crockett intoning text by Brazilian writer Beatrice Ezmer. Crockett returns on the turf

of Harlem Renaissance poet laureate Langston Hughes' "I, Too." Branker is quick to point out that the suite and its mutable definition of "place" relates to other oppressive geographic and ethnic conditions around the world. "Clearly," he comments, "we recognize that the voice Langston Hughes speaks through in his poem used in the movement 'I, Too, Sing America' is the voice of the African American community. However, if we

listen carefully, it will become clear that it can also be the voice of members of other disregarded groups within this country that clearly have the right to intone the words, 'I, Too, Am America.'"

In the instrumental component, driving yet sophisticated meshes of scored material slalom through themes, via a vibrant band including saxophonist Walter Smith III, trumpeter Remy le Beouf and guitarist Pete McCann. In some of the faster, more rhythmically intricate pieces in the suite, it's natural to detect qualities of the M-BASE movement, spearheaded by Steve Coleman, Greg Osby and others starting in 1980s Brooklyn. Although claiming no direct influence, Branker says, "I have probably been influenced by a lot of the same kinds of approaches and musical vibes that have inspired their way of knowing, experiencing, creating and communicating music. I am very moved by what I hear and the musical relationships that exist and evolve within these rhythmically complex and engaging compositions and improvisations. The work of M-BASE is crazy amazing."

Branker's musical lineage, as a first-generation American with parents from Trinidad and Barbados, includes Uncle Rupert, a music director and pianist with the Platters, and Uncle Roy, who wrote with Billy Strayhorn when both were with the Copasetics. Among the musical highlights in Branker's own career are a discography of a dozen-plus recordings and a role leading the Spirit of Life Ensemble, the regular Monday night band at Sweet Basil, the legendary Greenwich Village club of yore. A critical juncture in Branker's musical focus occurred in 1999, when he had a stroke during a big band rehearsal at Princeton. Two brain aneurysms and the discovery of AVM (arteriovenous malformation, the affliction from which guitarist Pat Martino suffered) guided him into writing, conceptualizing and conducting.

In his philosophy as a composer of jazz (however loosely defined), Branker points out that "the 'self' is always in relation to 'other,' and understanding that relationship as it occurs in a one-on-one situation or group setting and what happens when that becomes a main factor whether in a jazz group or in a classroom." As to his group Imagine, "This, for me as a composer, is infinitely more interesting and satisfying because the relationship between a composer and the performers can now be more collaborative and less heavy-handed from the perspective that a composer might have more of a tendency to want to dictate how a composition is 'supposed to be played.'"

Nearly a quarter century after his health crisis, Branker asserts, "I have grown quite a bit in my conceptual thinking, but I'm always trying to find new ways to continue this forward progress. There is so much that inspires me as a composer and I feel so incredibly energized and driven right now."

The project, Branker's eighth album for Origin Records, is imbued with the wisdom earned and musical lessons learned in his life as a veteran educator (currently at Rutgers, after retiring from Princeton), as a respected conductor for music by Wynton Marsalis, Terence Blanchard and Duke Ellington, and a composer/conceptualist. His powers in and commitment to that role grew dramatically after catastrophic health issues more-or-less ended his life as a trumpeter in 1999. The long, dedicated road has led Branker to this point, and he professes to be as creatively engaged and forward-thinking as ever. At 65, he asserts, "I feel as though I am just beginning to come into my own as a composer, so I just want to keep writing, learning, growing and sharing."

As for the story, or matrix of stories, told in his new suite, Branker explains that "the actual commitment to write this suite came after a period of seeing some incredibly disturbing images on television of the horrific suffering the citizens of Syria were experiencing during the country's ongoing civil war. This was when many were seeking refuge in a number of countries. Interestingly, though, I had been thinking about a number of issues associated with the concept of 'place,' such as what does place mean or represent, and how it is a universal concept that all of us can relate to on some level. "With all of this swirling around in my mind, I was driven to develop this extended work, which would allow me to offer my own creative responses to a number of historical and social occurrences. I could begin to unpack such overarching issues as inclusion and belonging while also addressing what I have described as circumstances of exploitation and zones of refuge experienced by people of color and other global citizens."

As Branker says, working in the broader canvas and modular strategy of creating a suite, versus discrete "tunes," has been an awakening process for him as a composer. He recalls the influence of a BMI Jazz Composers Workshop in the early 1990s, with innovative big band leaders Jim McNeely and Manny Albam, and McNeely's narrative vison of writing "with characters and episodes unfolding and developing time as part of the flow of a piece. It has been an eye-opening experience to embrace this kind of organizational thinking because I can approach the writing process in a more open, organic and episodic way. I could now start to consider things more like a visual artist would or a filmmaker who is imagining flow in more cinematic terms."

Fittingly, the suite's journey opens with "Door Of No Return," a reference to a slave trade shipping "place" in Senegal, with vocalist Alison Crockett intoning text by Brazilian writer Beatrice Ezmer. Crockett returns on the turf

of Harlem Renaissance poet laureate Langston Hughes' "I, Too." Branker is quick to point out that the suite and its mutable definition of "place" relates to other oppressive geographic and ethnic conditions around the world. "Clearly," he comments, "we recognize that the voice Langston Hughes speaks through in his poem used in the movement 'I, Too, Sing America' is the voice of the African American community. However, if we

listen carefully, it will become clear that it can also be the voice of members of other disregarded groups within this country that clearly have the right to intone the words, 'I, Too, Am America.'"

In the instrumental component, driving yet sophisticated meshes of scored material slalom through themes, via a vibrant band including saxophonist Walter Smith III, trumpeter Remy le Beouf and guitarist Pete McCann. In some of the faster, more rhythmically intricate pieces in the suite, it's natural to detect qualities of the M-BASE movement, spearheaded by Steve Coleman, Greg Osby and others starting in 1980s Brooklyn. Although claiming no direct influence, Branker says, "I have probably been influenced by a lot of the same kinds of approaches and musical vibes that have inspired their way of knowing, experiencing, creating and communicating music. I am very moved by what I hear and the musical relationships that exist and evolve within these rhythmically complex and engaging compositions and improvisations. The work of M-BASE is crazy amazing."

Branker's musical lineage, as a first-generation American with parents from Trinidad and Barbados, includes Uncle Rupert, a music director and pianist with the Platters, and Uncle Roy, who wrote with Billy Strayhorn when both were with the Copasetics. Among the musical highlights in Branker's own career are a discography of a dozen-plus recordings and a role leading the Spirit of Life Ensemble, the regular Monday night band at Sweet Basil, the legendary Greenwich Village club of yore. A critical juncture in Branker's musical focus occurred in 1999, when he had a stroke during a big band rehearsal at Princeton. Two brain aneurysms and the discovery of AVM (arteriovenous malformation, the affliction from which guitarist Pat Martino suffered) guided him into writing, conceptualizing and conducting.

In his philosophy as a composer of jazz (however loosely defined), Branker points out that "the 'self' is always in relation to 'other,' and understanding that relationship as it occurs in a one-on-one situation or group setting and what happens when that becomes a main factor whether in a jazz group or in a classroom." As to his group Imagine, "This, for me as a composer, is infinitely more interesting and satisfying because the relationship between a composer and the performers can now be more collaborative and less heavy-handed from the perspective that a composer might have more of a tendency to want to dictate how a composition is 'supposed to be played.'"

Nearly a quarter century after his health crisis, Branker asserts, "I have grown quite a bit in my conceptual thinking, but I'm always trying to find new ways to continue this forward progress. There is so much that inspires me as a composer and I feel so incredibly energized and driven right now."

Soundclips

Other Reviews of

"What Place Can Be for Us?":

All About Jazz (Italy) by Angelo Leonardi

Take Effect by Tom Haugen

All Music Guide by Matt Collar

Step Tempest by Richard Kamins

Textura by Ron Schepper

Jazzlands by Philip Booth

His Voice (Czech Republic) by Jan Hocek

Chicago Jazz Magazine by Jeff Cebulski

Nettavisen (Norway) by Thor Hammerø

All About Jazz by Michael Ambrosino

Paris Move by Thierry Docmac