MUSIC REVIEW BY Ken Dryden, New York City Jazz Record

Hal Galper has long been a part of the jazz scene, having recorded extensively as a leader over the past four decades and appearing on sessions by Sam Rivers, Phil Woods, Cannonball Adderley, Lee Konitz and Chet Baker, among others. Galper began with classical piano studies at an early age, spent time at Berklee and absorbed much from several Boston-based artists before leaving for New York City. Galper began leading his own groups in the ?70s. After establishing himself as a top postbop pianist, Galper quit touring for a time to develop his distinctive rubato method, which he now uses with his working trio.

The New York City Jazz Record: Tell me about your early exposure to jazz.

Hal Galper: I was failing miserably in high school, so they put me into vocational school to be an electrician and it was the only time I got ?A's. My parents got really excited and thought that I might become a scientist. The next year they sent me to this preparatory school in Copley Square in Boston. It was far above me and I had no idea what they were talking about most of the time. The Stables, a local club, was across the street. I'd go over during lunch and listen to Herb Pomeroy's group play and rehearse; I started taking bongo lessons from the janitor there and got really interested in the music. The last year I went back to regular high school and failed miserably but managed to graduate. In those days they had a state vocational rehabilitation board and they would check out disabled high school seniors. Having one eye qualified me for a scholarship, anyplace I wanted to go. My parents weren't going to pay for music school so I took the scholarship and went to Berklee over their strenuous objections.

TNYCJR: Berklee was in its infancy then.

HG: It was very small and you got great attention. It had a sense of camaraderie among students. Everybody was working together trying to help everyone else to learn. Information wasn't considered proprietary. I left after two-and-a-half years because the schedule was getting in the way of my practicing.

TNYCJR: Who were some of your earliest mentors?

HG: Herb Pomeroy for sure and Jaki Byard for damn sure! I took 18 lessons with Jaki. I probably learned the most with him, except for Sam Rivers. A couple of years later I looked in my notebooks and there was nothing in them. He [Byard] gave me my style of teaching, he swung you, he got you thinking about all kinds of stuff and you thought he was teaching you - actually you were teaching yourself. It was a very slick way of teaching. I studied twice with Ray Santisi, the piano player in Boston. He'd play and you'd watch and hopefully stop him and ask, "What was that"? I didn't know enough as a freshman to do that, but when I came back later I got a lot out of him. Sam Rivers was a major, major influence. We played together for six years and that was my postgraduate work. He really pushed the envelope and we were very much like minds and clicked immediately.

TNYCJR: I didn't realize that you and Phil Woods went back so many decades.

HG: Yeah, his was my first gig in New York City. I played in Phil's band from 1980 to 1990; it was a lot of fun. Phil recorded a number of my pieces and he was a great writer, too. Many bandleaders, like Chet Baker, couldn't write so they'd hire sidemen who could. When Chet found out that I wrote, that helped me get the gig. He recorded hundreds of versions of my songs, more than anybody.

TNYCJR: What was it like working with Baker?

HG: I was with him three years and it was my first big-time gig. Except for the drummer, bassist and me, it was a junkie band; my first experience working with junkies was an eye-opener. But I learned so much playing with Chet, even though he wouldn't be considered a teacher. He didn't have to say anything to teach you, all he had to do was play. His phrasing was...just amazing. He would be making up his own changes over the original set, which most great improvisers do. I didn't figure out how he did it for many years. I played duo with Lee Konitz for nine months and that was an incredible experience, but I'll have to say playing duo with Chet was not much fun. Lee didn't repeat himself once in nine months; all those guys of the Lennie Tristano school were really masterful improvisers.

TNYCJR: Why did you take time off from the road?

HG: I was working on my book The Touring Musician. There was a lot of pressure on me booking the band and doing the book, it just burned me out. I started the trio to create a laboratory for myself to find out how I wanted to play. I had many influences over the years, could play like anybody and have fun doing it. The audience would like it and it was a real problem for me. I needed to get to another technical level so I "got in the shed" from 2000 to 2005, doing very heavy practicing.

TNYCJR: How did you come to work with bassist Jeff Johnson and drummer John Bishop?

HG: I was playing the Port Townsend Jazz Festival and they put me together with Jeff and John Dean on drums. Jeff and I clicked immediately. Steve Ellington and I were looking for a bass player; we had gone through several after Todd Coolman, eating them up like candy. Being between Steve and myself was not an enviable position for a bassist because we go way back to Sam Rivers. We played a feature concert, then Jeff wrote me a letter, telling me how much he enjoyed playing with me. I had a tape of the concert and I listened to it again and called Steve and said, "I think we've found our bass player". When I started the trio again a few years ago, Jeff and John had been playing together for 20 years, so they were well-mated. But John had never played rubato before. It opened up something new for him that he's really excited about.

TNYCJR: What influenced your rubato style?

HG: Ornette Coleman's Double Quartet album Free Jazz was a great influence - everybody was playing rubato except the rhythm section. What's different now with this style is that Jeff and John are also playing rubato. It's been the trio's feeling that there have been a lot of advances in the music except rhythmically. Both Dizzy Gillespie and Lennie Tristano played odd time signatures within 4/4, not as a separate thing. In regular playing you had a background and a foreground, a simple, bouncy quarter-note background that clarified anything that was going on in the frontline. In the case with the trio, there is no background, we're all foreground, it's group improv, like Dixieland.

TNYCJR: Tell me how it came about.

HG: My usual way of practicing was to avoid it until 11:30 pm and then go to the piano. This sort of crept out, I didn't plan it and I thought this feels really right, really good. I had no idea what it was, but felt that I'd never find anybody to play it with. As an experiment I got a night at the Deerhead Inn with Tony Marino on bass as a duo, who I didn't know was at heart a free player. It clicked immediately. We had a rather geriatric audience and I thought it would turn them off, but they loved it because we were still using the vocabulary of the music, the same licks we've been playing for years but our way. The older audiences are much better educated than the younger ones because they were part of the scene that made jazz happen. Then I thought I'd never find a drummer. Billy Mintz had done a couple of records with Jeff Johnson and his name popped up playing at a church in New York. I ran him down, got him for a gig and it worked perfectly. That was two people I could play with, now I have six. I was kind of surprised at my direction, so I went over my recordings to do a retrospective and I noticed how often I would go into that mode for short periods, so it has been there all the time, but I used it judiciously. I'd suddenly break into rubato playing in the middle of a solo. It's been there all the time and kept developing, but I never focused on it.

TNYCJR: How does a new piece evolve for you?

HG: Sometimes I'll copy something I played or I'll have one phrase, a germ of an idea. I'll write them down in a notebook and revisit them to see if I can do anything with them. I had one for 50 years that I couldn't find a use for that I finally used last year. I've been doing a lot of studying of Brazilian harmony and it fell right in with my studies. Sometimes it takes years to write a tune and others just drip off your fingers.

For more information, visit halgalper.com

The New York City Jazz Record: Tell me about your early exposure to jazz.

Hal Galper: I was failing miserably in high school, so they put me into vocational school to be an electrician and it was the only time I got ?A's. My parents got really excited and thought that I might become a scientist. The next year they sent me to this preparatory school in Copley Square in Boston. It was far above me and I had no idea what they were talking about most of the time. The Stables, a local club, was across the street. I'd go over during lunch and listen to Herb Pomeroy's group play and rehearse; I started taking bongo lessons from the janitor there and got really interested in the music. The last year I went back to regular high school and failed miserably but managed to graduate. In those days they had a state vocational rehabilitation board and they would check out disabled high school seniors. Having one eye qualified me for a scholarship, anyplace I wanted to go. My parents weren't going to pay for music school so I took the scholarship and went to Berklee over their strenuous objections.

TNYCJR: Berklee was in its infancy then.

HG: It was very small and you got great attention. It had a sense of camaraderie among students. Everybody was working together trying to help everyone else to learn. Information wasn't considered proprietary. I left after two-and-a-half years because the schedule was getting in the way of my practicing.

TNYCJR: Who were some of your earliest mentors?

HG: Herb Pomeroy for sure and Jaki Byard for damn sure! I took 18 lessons with Jaki. I probably learned the most with him, except for Sam Rivers. A couple of years later I looked in my notebooks and there was nothing in them. He [Byard] gave me my style of teaching, he swung you, he got you thinking about all kinds of stuff and you thought he was teaching you - actually you were teaching yourself. It was a very slick way of teaching. I studied twice with Ray Santisi, the piano player in Boston. He'd play and you'd watch and hopefully stop him and ask, "What was that"? I didn't know enough as a freshman to do that, but when I came back later I got a lot out of him. Sam Rivers was a major, major influence. We played together for six years and that was my postgraduate work. He really pushed the envelope and we were very much like minds and clicked immediately.

TNYCJR: I didn't realize that you and Phil Woods went back so many decades.

HG: Yeah, his was my first gig in New York City. I played in Phil's band from 1980 to 1990; it was a lot of fun. Phil recorded a number of my pieces and he was a great writer, too. Many bandleaders, like Chet Baker, couldn't write so they'd hire sidemen who could. When Chet found out that I wrote, that helped me get the gig. He recorded hundreds of versions of my songs, more than anybody.

TNYCJR: What was it like working with Baker?

HG: I was with him three years and it was my first big-time gig. Except for the drummer, bassist and me, it was a junkie band; my first experience working with junkies was an eye-opener. But I learned so much playing with Chet, even though he wouldn't be considered a teacher. He didn't have to say anything to teach you, all he had to do was play. His phrasing was...just amazing. He would be making up his own changes over the original set, which most great improvisers do. I didn't figure out how he did it for many years. I played duo with Lee Konitz for nine months and that was an incredible experience, but I'll have to say playing duo with Chet was not much fun. Lee didn't repeat himself once in nine months; all those guys of the Lennie Tristano school were really masterful improvisers.

TNYCJR: Why did you take time off from the road?

HG: I was working on my book The Touring Musician. There was a lot of pressure on me booking the band and doing the book, it just burned me out. I started the trio to create a laboratory for myself to find out how I wanted to play. I had many influences over the years, could play like anybody and have fun doing it. The audience would like it and it was a real problem for me. I needed to get to another technical level so I "got in the shed" from 2000 to 2005, doing very heavy practicing.

TNYCJR: How did you come to work with bassist Jeff Johnson and drummer John Bishop?

HG: I was playing the Port Townsend Jazz Festival and they put me together with Jeff and John Dean on drums. Jeff and I clicked immediately. Steve Ellington and I were looking for a bass player; we had gone through several after Todd Coolman, eating them up like candy. Being between Steve and myself was not an enviable position for a bassist because we go way back to Sam Rivers. We played a feature concert, then Jeff wrote me a letter, telling me how much he enjoyed playing with me. I had a tape of the concert and I listened to it again and called Steve and said, "I think we've found our bass player". When I started the trio again a few years ago, Jeff and John had been playing together for 20 years, so they were well-mated. But John had never played rubato before. It opened up something new for him that he's really excited about.

TNYCJR: What influenced your rubato style?

HG: Ornette Coleman's Double Quartet album Free Jazz was a great influence - everybody was playing rubato except the rhythm section. What's different now with this style is that Jeff and John are also playing rubato. It's been the trio's feeling that there have been a lot of advances in the music except rhythmically. Both Dizzy Gillespie and Lennie Tristano played odd time signatures within 4/4, not as a separate thing. In regular playing you had a background and a foreground, a simple, bouncy quarter-note background that clarified anything that was going on in the frontline. In the case with the trio, there is no background, we're all foreground, it's group improv, like Dixieland.

TNYCJR: Tell me how it came about.

HG: My usual way of practicing was to avoid it until 11:30 pm and then go to the piano. This sort of crept out, I didn't plan it and I thought this feels really right, really good. I had no idea what it was, but felt that I'd never find anybody to play it with. As an experiment I got a night at the Deerhead Inn with Tony Marino on bass as a duo, who I didn't know was at heart a free player. It clicked immediately. We had a rather geriatric audience and I thought it would turn them off, but they loved it because we were still using the vocabulary of the music, the same licks we've been playing for years but our way. The older audiences are much better educated than the younger ones because they were part of the scene that made jazz happen. Then I thought I'd never find a drummer. Billy Mintz had done a couple of records with Jeff Johnson and his name popped up playing at a church in New York. I ran him down, got him for a gig and it worked perfectly. That was two people I could play with, now I have six. I was kind of surprised at my direction, so I went over my recordings to do a retrospective and I noticed how often I would go into that mode for short periods, so it has been there all the time, but I used it judiciously. I'd suddenly break into rubato playing in the middle of a solo. It's been there all the time and kept developing, but I never focused on it.

TNYCJR: How does a new piece evolve for you?

HG: Sometimes I'll copy something I played or I'll have one phrase, a germ of an idea. I'll write them down in a notebook and revisit them to see if I can do anything with them. I had one for 50 years that I couldn't find a use for that I finally used last year. I've been doing a lot of studying of Brazilian harmony and it fell right in with my studies. Sometimes it takes years to write a tune and others just drip off your fingers.

For more information, visit halgalper.com

Soundclips

Other Reviews of

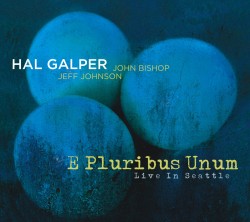

"E Pluribus Unum - Live in Seattle":

Jazzmozaïek - Belgium by Marc Van de Walle

All Music Guide by Ken Dryden

Audiophile Audition by Ethan Krow

JazzChicago.net by Brad Walseth

Jazziz, Summer 2010 by Bob Weinberg

JazzTimes by Bill Milkowski

Rifftides by Doug Ramsey

All About Jazz by Dan McClenaghan

The Denver Post by Bret Saunders