MUSIC REVIEW BY Optimism One, The Normal School Literary Magazine

WORD MUSIC: A DISCUSSION WITH BENJAMIN BOONE

The definitions of music and poetry are similar enough to trouble distinction. In fact, descriptions of poetry often, if not always, include allusions to its musical qualities - its rhythms, its repetitions, its tone, its accents—all words that could also describe a song. And the formal study of poetry, even in our modern privileging of free verse, still includes at least some discussion of prosody, "the patterns of rhythm and sound used in poetry." Those musical qualities might explain why poetry is often better heard than read, just like the average person would prefer hearing a song rather than reading its notes from a sheet.

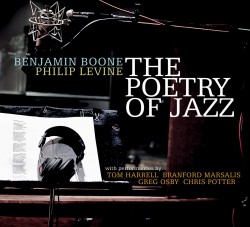

Given the common ground between the two art forms, it is no surprise, then, that creatives throughout history have combined music with poetry, poetry with music. And that pursuit continues today, whether it is at your local open mic, the Lincoln Center in New York City, or on record. A recent example of the latter can be found on The Poetry of Jazz, a collaboration between saxophonist Benjamin Boone and the late poet Philip Levine.

It deserve deep and repeated listening, but before doing so, readers, writers, and musicians alike can find great inspiration from hearing Benjamin Boone discuss his project.

OO: To start, will you talk about your relationship with the writer whose words grace your album and why you wanted to make this record?

Ben: I only knew Philip three or four years, and our conversations revolved mostly around jazz. I met Phil when I was asked to do a fundraising concert where he would be reading. I called Phil and asked if he wanted to collaborate, rather than do separate sets. Of course, I knew about Philip Levine even before I moved to Fresno. My writer friend Danny Foltz-Gray first introduced his work to me in 2000. I had asked him whether I should consider applying to California State University Fresno, and he said, "Fresno? My absolute favorite living poet teaches there, Philip Levine! If they have retained Philip Levine all this time, it must be a great place."

So I checked out Phil's work and there was an immediacy to it that resonated with me. I love that his poems speak of the working class, of toil and drudgery, genocide, race relations, and what work truly is. All as relevant today as ever. And the poems were understandable, at least on some level, to non-poets like me. I also fell in love with the musicality of his voice. My dissertation dealt with a musical analysis of speech, and I could certainly hear music in Phil's recitations. They were more like performances. So we did the concert and then decided to see what a recording would sound like. That experiment was a success, so over the next three years - almost right until his death - we recorded twenty-nine of his poems with music.

OO: You're working with Philip Levine's completed poems while playing in a traditional, albeit expansive, jazz format. Can you tell us about the freedoms and challenges of your chosen approach?

Well, you are right, Op. I knew from the moment we began the collaboration that Jazz would be the main musical style. I'm a classical composer and a jazz saxophonist, and Phil had gone to school in Detroit with jazz greats Kenny Burrell, Pepper Adams, Bess Bonier, Tommy Flanagan, and Barry Harris. One of his teachers was Harold McGee, who played with Charlie Parker among many others. He was a true jazz lover who understood and appreciated jazz on a deep level, so jazz records, musicians, and concerts were what we talked about. It was our common thread. So I knew a jazz quartet would be the core ensemble. But within that restriction was freedom to alter the sound world and the style for each track to form an appropriate setting for each poem. I didn't feel restricted at all. The challenges were all compositional - how to amplify the meaning of the poem with music or how to sustain an emotion for a really long time - not stylistic. I am a huge fan of composer Igor Stravinsky, and he supposedly said, "In music, freedom is found within the bounds of restriction." I think the tracks on this disc demonstrate this quite nicely.

OO: Aside from your primary collaborator, Philip, can you tell us about those who contributed to your project and why you chose them?

Well, this question piggie-backs on the last one, because I used several guest musicians to help each track sound unique and add to the core sound of Phil with a jazz quartet. For example, I brought in a second pianist, Craig von Berg, for specific tracks because I think he plays the piano as an orchestra, doing things like adding crazy piano sounds to "A Dozen Dawn Songs Plus One." I ended up using three bass players, two drummers, and two pianists, all in an effort to make the sound of each track unique. I also added German violinist Stefan Poetzch to both "Dawn Songs" and "Our Valley." In "By the Water of the Llobregat," I used only solo piano and wrote out every note. Singer Karen Marguth added vocalizations to "Gin" and "Music of Time." My sons, Atticus and Asher Boone, joined me to form the backup "horn section" on "I Remember Clifford," and Max Hembd added harmony parts on several tracks.

I also decided to have some jazz superstars replace me on four tracks about jazz greats Sonny Rollins, John Coltrane, Charlie Parker and Clifford Brown. I recall listening to what I thought was the final version of "I Remember Clifford" about trumpet legend Clifford Brown. I thought, "It's just wrong for me, a saxophonist, to be taking the lead on this track." So my producer extraordinaire Donald Brown got famed New York trumpeter Tom Harrell, who was deeply influenced by Brown, to do it. That logic extended to Chris Potter, who gets the big sound of Sonny Rollins, replacing my playing on "The Unknowable" about Rollins' hiatus from the public eye. Greg Osby, who sounds like what Charlie Parker would have sounded like had he lived longer, replaced me on "Call It Music," a poem that recounts a story related to Levine by his teacher, Harold McGee, the trumpeter at the famed Dial recording session of "Lover Man," where Parker was intoxicated. And lastly, Branford Marsalis, who I knew through a connection with the New Century Saxophone Quartet's Steve Pollock, recorded "Soloing," in which Levine compares his aging mother's isolated existence to a Coltrane solo.

It was tempting to have them play on more than one track, but that would have defeated my primary reason for having them on these particular tracks. Donald Brown and Mike Marciano, the primary mixer, helped create unique sounds for each track in the mixing process too. All these folks chimed in with ideas and helped shape what you hear on the disc. On Volume II, you will be able to hear more of our freely improvised playing, and you can hear the synergy between the band and Phil even more.

OO: What records that combine music and poetry - or even more mainstream records - inspired you or at least resonated in the back of your mind while writing and recording this album?

When I first knew I would be collaborating with Phil, I did investigate several recordings of poets with musicians. But frankly, the lessons I learned from many of them is what I did not want to do, rather than serve as model for what I wanted to do. To my musical ear, the music was all too often reacting to surface-level action of the poems - doing "word painting." In others it sounded to me more like a books on tape - the music was only an underscore to the reading. That is okay, and I know many people like many of these collaborations, but it's not interesting for me as a composer or a performer. Instead my inspiration musically was from the jazz canon.

OO: What were the guiding questions or themes you had when you began the project?

I decided early on that if I were to do this, my self-imposed challenge would be to find a way music could enhance the central meaning of each poem and have the music be an equal partner in communicating that emotion. The listener must experience the words in a different way than if it were a reading. One of my thoughts was that music can give the listener time to contemplate what they have heard - time for it sink beneath the surface - time for the listener to feel on a deeper level what is being expressed. This is especially true in poems like "By the Waters of the Llobregat" about genocide (listen to the long sustains in the piano), or "What Work Is" (which compels us to think of lost opportunities with loved ones), or "A Dozen Dawn Songs Plus One" (aid in digesting the horrid existence of workers). If the music doesn't enhance the poem and give it added value in some real way, and serve as an equal partner, then to me it's not artistically interesting - at least for the duration of an entire CD.

Another guiding question for me was, "What can I learn from Phil Levine?" I love interdisciplinary collaborations and always grow from them, and there I was living only two miles from a Pulitzer Prize winning poet. So I wanted to learn and grow from making art with Phil. And indeed I learned a great deal about truth-telling, emotional honesty, flow, pacing, and mostly being confident in myself as an artist.

The famous opera composer Jake Heggie says that successful collaborations stem from the stakeholders consciously drawing from the same emotional well. Phil and I didn't discuss this but we both have a true love of music, a respect for jazz and of the emotional worlds it creates, and a love of the music of words, and so we drew on that throughout the process.

OO: What did you discover in the process that surprised you?

Well, firstly, I discovered even deeper meanings to Phil's poems. They are like Baroque music - the deeper you look, the more you find. I discovered ways music can interact with poetry to enhance the poetry. I had to throw away lots of music I really liked in the best interest of the poem. But mostly, I discovered, and this is directly from my interactions with Phil, a level of self-confidence that had been lacking.

Phil taught me so much, not only about poetry and how to be a creative artist, but perhaps more importantly to tamp down my inner anxiety and insecurity and believe in myself and my creativity. This gave me the courage to ask top musicians in the world to collaborate on the project and to really push this CD.

OO: Since you've also written and recorded albums that were not collaborations with poets, how would you compare those experiences with the writing and recording of this?

If you give yourself a unique creative challenge, then you have to think in new ways to make that work, and hopefully that makes the end result fresh to both you and the audience. So though I've written for opera, orchestras, jazz singers, music theater, classical instrumentalists, and jazz groups, this was a unique and special project. I think it is fresh. I had to think very hard about leaving space for the words to be heard, and how to keep energy going in a different way. How is this for a challenge?: Write music that allows people to process genocide, or the horror and violence of race relations. You have to think in new ways.

OO: How do you think the writing and recording of this album will influence your future writing and recording that does not combine music with poetry?

Great question and one that I probably won't be able to answer until I look back in five years and have a clearer perspective. But I suppose I am even more aware of the underlying intent behind a song, sort of like what Brian is talking about when he spoke of creating a positive space - a space full of potential - and also what he said about the music coming from a deep emotional place.

Right now, I am in Ghana, immersing myself in the world of complicated polyrhythms, which is a huge challenge to me. What they can do blows my mind. How they think of music and perceive beat is so different than how I do. I can't see beyond that right now!

OO: Since you are connected with Fresno, which has such a rich literary history and which is such a unique place that is represented in its literature, in what ways does place - the location where you created or recorded these compositions or even the locations addressed in the words - factor into the album?

I think the clearest example on this project is the poem "Our Valley." My challenge was to somehow create the sense of expansiveness, space, and searing heat Phil describes so well. I've lived in Fresno eighteen years now and know exactly what he was trying to show. I also intimately know the music of the jazz greats he mentions, so I was able to channel those sounds, and have been in factories, and have worked construction, washed dishes, dug ditches, and other hard-labor jobs, so I think I was better able to channel those feelings into the music. At its core, this is a Fresno CD. It was born from a fundraiser for Fresno Filmworks; it was championed by KFSR, local art critic Donald Munro, former Fresnan Sasha Khokha, and Valley Public Radio's Joe Moore; it was supported by Fresno State and the Dean's Council of the College of Arts and Humanities; and it was recorded at Maximus Media in Fresno. Also, almost everyone on the CD lives or lived in Fresno. Phil and I performed there for local audiences at the Rogue Festival, and a huge focus group of Fresno musicians and poets critiqued the project all along the way and helped shape it. Fresno knows hard work, and hard work was put into the project by the people of Fresno. It is in every track.

OO: Because the sounds of words matter so much, particularly for poets, in what ways did the notes and sounds you chose to play represent the words in conversation with the actual words?

I mentioned before that I hear speech as music and that my dissertation analyzed speech as music, so this is a topic near and dear to my heart. I did not transcribe Phil's recitations into music for this project, but I could tell that Phil, because he was a musician at heart, altered his tempo, dynamics, timbre, and pitch contour to match the music of the band. And the musicians instinctively did the same. You can clearly hear this on all tracks, but especially on the track "Gin." Compositionally, on all the tracks, I used the tempo I thought appropriate and gave Phil clear directions on when to start, when to pause and for how long, and places he should listen for musical cues. If you want to blow your mind, read about the psychological phenomenon of rhythmic synchrony. I think our tracks demonstrate this phenomenon quite well. We were in total sync in the studio, so we imitated each other naturally.

I did literally and consciously use Phil's speech as a musical instrument in my orchestral composition, "Waterless Music," that I wrote shortly after Phil died, and is dedicated to his memory. From the recordings made for The Poetry of Jazz, I took excerpts, grouped them by topic, and put them together to form a narrative about water, life, and the environment. Here is a link to that video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mQ4KUSQYvSk. In this piece, you can hear Phil's voice used literally like an instrument.

OO: Why is it important for these types of art - music and poetry, combined or separate - to continue pushing the boundaries of traditional forms?

Steven Johnson, in his book How We Got to Now, discusses the conditions necessary for life to have evolved and for good ideas to take root. One is that ideas need to clash. A proper environment needs to be created where elements rub against each other. This is how I view interdisciplinary collaboration. It is fertile territory. So I am in no way trying to be a radical and push any real boundaries, or even thinking about whether the forms I am creating are new or not. These are just natural outgrowths of thinking of the artistic creation. One of the reasons I am in Ghana is so my perspectives and biases and preconceptions can rub up against another culture so I can become more self-aware, more empathic, and grow.

I mentioned before that I am in a group now with xylophonists who think of music in a completely different way than I do, and I love it. My head hurts as I try and play what they play, and I am better for it. I think it was Oliver Wendell Holmes who said, "A mind expanded can never retract to its original dimensions." Well, interdisciplinary collaboration expands my mind and I hope it never retracts. As for influencing the art form, it would be cool to me if more folks did interdisciplinary work. In fact, several poetry and jazz projects have been released recently. Steven Johnson, the historian, would say this is how ideas happen; many people get the same basic idea at once. Go figure.

OO: Can you tell us more about how you plan to explore the connections between music and poetry in the future?

There are fifteen tracks I recorded with Phil that are not on The Poetry of Jazz, and these, as well as three instrumental versions of these tunes, will be released on a Volume II.

For another poetry-music project, I've recorded with Fresno State colleague and US Poet Laureate Juan Felipe Herrera, as well as Marisol Baca, Lee Herrick, and Dustin Prestridge. That was an amazing experience, and we will release that on CD, tentatively titled The Poets Are Gathering, at some point. Congolese poet Fiston Mujila Fiston, now in Austria, heard The Poetry of Jazz, and we are hoping to collaborate at some point. I love doing these type of projects, and I hope there will be many more.

The definitions of music and poetry are similar enough to trouble distinction. In fact, descriptions of poetry often, if not always, include allusions to its musical qualities - its rhythms, its repetitions, its tone, its accents—all words that could also describe a song. And the formal study of poetry, even in our modern privileging of free verse, still includes at least some discussion of prosody, "the patterns of rhythm and sound used in poetry." Those musical qualities might explain why poetry is often better heard than read, just like the average person would prefer hearing a song rather than reading its notes from a sheet.

Given the common ground between the two art forms, it is no surprise, then, that creatives throughout history have combined music with poetry, poetry with music. And that pursuit continues today, whether it is at your local open mic, the Lincoln Center in New York City, or on record. A recent example of the latter can be found on The Poetry of Jazz, a collaboration between saxophonist Benjamin Boone and the late poet Philip Levine.

It deserve deep and repeated listening, but before doing so, readers, writers, and musicians alike can find great inspiration from hearing Benjamin Boone discuss his project.

OO: To start, will you talk about your relationship with the writer whose words grace your album and why you wanted to make this record?

Ben: I only knew Philip three or four years, and our conversations revolved mostly around jazz. I met Phil when I was asked to do a fundraising concert where he would be reading. I called Phil and asked if he wanted to collaborate, rather than do separate sets. Of course, I knew about Philip Levine even before I moved to Fresno. My writer friend Danny Foltz-Gray first introduced his work to me in 2000. I had asked him whether I should consider applying to California State University Fresno, and he said, "Fresno? My absolute favorite living poet teaches there, Philip Levine! If they have retained Philip Levine all this time, it must be a great place."

So I checked out Phil's work and there was an immediacy to it that resonated with me. I love that his poems speak of the working class, of toil and drudgery, genocide, race relations, and what work truly is. All as relevant today as ever. And the poems were understandable, at least on some level, to non-poets like me. I also fell in love with the musicality of his voice. My dissertation dealt with a musical analysis of speech, and I could certainly hear music in Phil's recitations. They were more like performances. So we did the concert and then decided to see what a recording would sound like. That experiment was a success, so over the next three years - almost right until his death - we recorded twenty-nine of his poems with music.

OO: You're working with Philip Levine's completed poems while playing in a traditional, albeit expansive, jazz format. Can you tell us about the freedoms and challenges of your chosen approach?

Well, you are right, Op. I knew from the moment we began the collaboration that Jazz would be the main musical style. I'm a classical composer and a jazz saxophonist, and Phil had gone to school in Detroit with jazz greats Kenny Burrell, Pepper Adams, Bess Bonier, Tommy Flanagan, and Barry Harris. One of his teachers was Harold McGee, who played with Charlie Parker among many others. He was a true jazz lover who understood and appreciated jazz on a deep level, so jazz records, musicians, and concerts were what we talked about. It was our common thread. So I knew a jazz quartet would be the core ensemble. But within that restriction was freedom to alter the sound world and the style for each track to form an appropriate setting for each poem. I didn't feel restricted at all. The challenges were all compositional - how to amplify the meaning of the poem with music or how to sustain an emotion for a really long time - not stylistic. I am a huge fan of composer Igor Stravinsky, and he supposedly said, "In music, freedom is found within the bounds of restriction." I think the tracks on this disc demonstrate this quite nicely.

OO: Aside from your primary collaborator, Philip, can you tell us about those who contributed to your project and why you chose them?

Well, this question piggie-backs on the last one, because I used several guest musicians to help each track sound unique and add to the core sound of Phil with a jazz quartet. For example, I brought in a second pianist, Craig von Berg, for specific tracks because I think he plays the piano as an orchestra, doing things like adding crazy piano sounds to "A Dozen Dawn Songs Plus One." I ended up using three bass players, two drummers, and two pianists, all in an effort to make the sound of each track unique. I also added German violinist Stefan Poetzch to both "Dawn Songs" and "Our Valley." In "By the Water of the Llobregat," I used only solo piano and wrote out every note. Singer Karen Marguth added vocalizations to "Gin" and "Music of Time." My sons, Atticus and Asher Boone, joined me to form the backup "horn section" on "I Remember Clifford," and Max Hembd added harmony parts on several tracks.

I also decided to have some jazz superstars replace me on four tracks about jazz greats Sonny Rollins, John Coltrane, Charlie Parker and Clifford Brown. I recall listening to what I thought was the final version of "I Remember Clifford" about trumpet legend Clifford Brown. I thought, "It's just wrong for me, a saxophonist, to be taking the lead on this track." So my producer extraordinaire Donald Brown got famed New York trumpeter Tom Harrell, who was deeply influenced by Brown, to do it. That logic extended to Chris Potter, who gets the big sound of Sonny Rollins, replacing my playing on "The Unknowable" about Rollins' hiatus from the public eye. Greg Osby, who sounds like what Charlie Parker would have sounded like had he lived longer, replaced me on "Call It Music," a poem that recounts a story related to Levine by his teacher, Harold McGee, the trumpeter at the famed Dial recording session of "Lover Man," where Parker was intoxicated. And lastly, Branford Marsalis, who I knew through a connection with the New Century Saxophone Quartet's Steve Pollock, recorded "Soloing," in which Levine compares his aging mother's isolated existence to a Coltrane solo.

It was tempting to have them play on more than one track, but that would have defeated my primary reason for having them on these particular tracks. Donald Brown and Mike Marciano, the primary mixer, helped create unique sounds for each track in the mixing process too. All these folks chimed in with ideas and helped shape what you hear on the disc. On Volume II, you will be able to hear more of our freely improvised playing, and you can hear the synergy between the band and Phil even more.

OO: What records that combine music and poetry - or even more mainstream records - inspired you or at least resonated in the back of your mind while writing and recording this album?

When I first knew I would be collaborating with Phil, I did investigate several recordings of poets with musicians. But frankly, the lessons I learned from many of them is what I did not want to do, rather than serve as model for what I wanted to do. To my musical ear, the music was all too often reacting to surface-level action of the poems - doing "word painting." In others it sounded to me more like a books on tape - the music was only an underscore to the reading. That is okay, and I know many people like many of these collaborations, but it's not interesting for me as a composer or a performer. Instead my inspiration musically was from the jazz canon.

OO: What were the guiding questions or themes you had when you began the project?

I decided early on that if I were to do this, my self-imposed challenge would be to find a way music could enhance the central meaning of each poem and have the music be an equal partner in communicating that emotion. The listener must experience the words in a different way than if it were a reading. One of my thoughts was that music can give the listener time to contemplate what they have heard - time for it sink beneath the surface - time for the listener to feel on a deeper level what is being expressed. This is especially true in poems like "By the Waters of the Llobregat" about genocide (listen to the long sustains in the piano), or "What Work Is" (which compels us to think of lost opportunities with loved ones), or "A Dozen Dawn Songs Plus One" (aid in digesting the horrid existence of workers). If the music doesn't enhance the poem and give it added value in some real way, and serve as an equal partner, then to me it's not artistically interesting - at least for the duration of an entire CD.

Another guiding question for me was, "What can I learn from Phil Levine?" I love interdisciplinary collaborations and always grow from them, and there I was living only two miles from a Pulitzer Prize winning poet. So I wanted to learn and grow from making art with Phil. And indeed I learned a great deal about truth-telling, emotional honesty, flow, pacing, and mostly being confident in myself as an artist.

The famous opera composer Jake Heggie says that successful collaborations stem from the stakeholders consciously drawing from the same emotional well. Phil and I didn't discuss this but we both have a true love of music, a respect for jazz and of the emotional worlds it creates, and a love of the music of words, and so we drew on that throughout the process.

OO: What did you discover in the process that surprised you?

Well, firstly, I discovered even deeper meanings to Phil's poems. They are like Baroque music - the deeper you look, the more you find. I discovered ways music can interact with poetry to enhance the poetry. I had to throw away lots of music I really liked in the best interest of the poem. But mostly, I discovered, and this is directly from my interactions with Phil, a level of self-confidence that had been lacking.

Phil taught me so much, not only about poetry and how to be a creative artist, but perhaps more importantly to tamp down my inner anxiety and insecurity and believe in myself and my creativity. This gave me the courage to ask top musicians in the world to collaborate on the project and to really push this CD.

OO: Since you've also written and recorded albums that were not collaborations with poets, how would you compare those experiences with the writing and recording of this?

If you give yourself a unique creative challenge, then you have to think in new ways to make that work, and hopefully that makes the end result fresh to both you and the audience. So though I've written for opera, orchestras, jazz singers, music theater, classical instrumentalists, and jazz groups, this was a unique and special project. I think it is fresh. I had to think very hard about leaving space for the words to be heard, and how to keep energy going in a different way. How is this for a challenge?: Write music that allows people to process genocide, or the horror and violence of race relations. You have to think in new ways.

OO: How do you think the writing and recording of this album will influence your future writing and recording that does not combine music with poetry?

Great question and one that I probably won't be able to answer until I look back in five years and have a clearer perspective. But I suppose I am even more aware of the underlying intent behind a song, sort of like what Brian is talking about when he spoke of creating a positive space - a space full of potential - and also what he said about the music coming from a deep emotional place.

Right now, I am in Ghana, immersing myself in the world of complicated polyrhythms, which is a huge challenge to me. What they can do blows my mind. How they think of music and perceive beat is so different than how I do. I can't see beyond that right now!

OO: Since you are connected with Fresno, which has such a rich literary history and which is such a unique place that is represented in its literature, in what ways does place - the location where you created or recorded these compositions or even the locations addressed in the words - factor into the album?

I think the clearest example on this project is the poem "Our Valley." My challenge was to somehow create the sense of expansiveness, space, and searing heat Phil describes so well. I've lived in Fresno eighteen years now and know exactly what he was trying to show. I also intimately know the music of the jazz greats he mentions, so I was able to channel those sounds, and have been in factories, and have worked construction, washed dishes, dug ditches, and other hard-labor jobs, so I think I was better able to channel those feelings into the music. At its core, this is a Fresno CD. It was born from a fundraiser for Fresno Filmworks; it was championed by KFSR, local art critic Donald Munro, former Fresnan Sasha Khokha, and Valley Public Radio's Joe Moore; it was supported by Fresno State and the Dean's Council of the College of Arts and Humanities; and it was recorded at Maximus Media in Fresno. Also, almost everyone on the CD lives or lived in Fresno. Phil and I performed there for local audiences at the Rogue Festival, and a huge focus group of Fresno musicians and poets critiqued the project all along the way and helped shape it. Fresno knows hard work, and hard work was put into the project by the people of Fresno. It is in every track.

OO: Because the sounds of words matter so much, particularly for poets, in what ways did the notes and sounds you chose to play represent the words in conversation with the actual words?

I mentioned before that I hear speech as music and that my dissertation analyzed speech as music, so this is a topic near and dear to my heart. I did not transcribe Phil's recitations into music for this project, but I could tell that Phil, because he was a musician at heart, altered his tempo, dynamics, timbre, and pitch contour to match the music of the band. And the musicians instinctively did the same. You can clearly hear this on all tracks, but especially on the track "Gin." Compositionally, on all the tracks, I used the tempo I thought appropriate and gave Phil clear directions on when to start, when to pause and for how long, and places he should listen for musical cues. If you want to blow your mind, read about the psychological phenomenon of rhythmic synchrony. I think our tracks demonstrate this phenomenon quite well. We were in total sync in the studio, so we imitated each other naturally.

I did literally and consciously use Phil's speech as a musical instrument in my orchestral composition, "Waterless Music," that I wrote shortly after Phil died, and is dedicated to his memory. From the recordings made for The Poetry of Jazz, I took excerpts, grouped them by topic, and put them together to form a narrative about water, life, and the environment. Here is a link to that video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mQ4KUSQYvSk. In this piece, you can hear Phil's voice used literally like an instrument.

OO: Why is it important for these types of art - music and poetry, combined or separate - to continue pushing the boundaries of traditional forms?

Steven Johnson, in his book How We Got to Now, discusses the conditions necessary for life to have evolved and for good ideas to take root. One is that ideas need to clash. A proper environment needs to be created where elements rub against each other. This is how I view interdisciplinary collaboration. It is fertile territory. So I am in no way trying to be a radical and push any real boundaries, or even thinking about whether the forms I am creating are new or not. These are just natural outgrowths of thinking of the artistic creation. One of the reasons I am in Ghana is so my perspectives and biases and preconceptions can rub up against another culture so I can become more self-aware, more empathic, and grow.

I mentioned before that I am in a group now with xylophonists who think of music in a completely different way than I do, and I love it. My head hurts as I try and play what they play, and I am better for it. I think it was Oliver Wendell Holmes who said, "A mind expanded can never retract to its original dimensions." Well, interdisciplinary collaboration expands my mind and I hope it never retracts. As for influencing the art form, it would be cool to me if more folks did interdisciplinary work. In fact, several poetry and jazz projects have been released recently. Steven Johnson, the historian, would say this is how ideas happen; many people get the same basic idea at once. Go figure.

OO: Can you tell us more about how you plan to explore the connections between music and poetry in the future?

There are fifteen tracks I recorded with Phil that are not on The Poetry of Jazz, and these, as well as three instrumental versions of these tunes, will be released on a Volume II.

For another poetry-music project, I've recorded with Fresno State colleague and US Poet Laureate Juan Felipe Herrera, as well as Marisol Baca, Lee Herrick, and Dustin Prestridge. That was an amazing experience, and we will release that on CD, tentatively titled The Poets Are Gathering, at some point. Congolese poet Fiston Mujila Fiston, now in Austria, heard The Poetry of Jazz, and we are hoping to collaborate at some point. I love doing these type of projects, and I hope there will be many more.

Soundclips

Other Reviews of

"The Poetry of Jazz":

JazzDaGama by Raul da Gama

All About Jazz by DUNCAN HEINING

The Jazz Duck by Editor

JazzTimes by Britt Robson

Step Tempest by Richard Kamins

Downbeat by Michael Jackson

Jazz Weekly by George W. Harris

The Aquarian by Mike Greenblatt

Improvijazzation Nation by Rotcod Zzaj

New York City Jazz Record by John Pietaro

The Paris Review by Jeffery Gleaves

JazzTimes by Andrew Gilbert

NPR - All Things Considered by Tom Vitale

All About Jazz by Mark Corroto

Fresno Bee by Joshua Tehee