MUSIC REVIEW BY Benjamin Kirk, Fresno State College of Arts & Humanities

It was hot! It was the summer of 2018 in the city of Accra, about 400 miles north of the equator, and Benjamin Boone and the Ghana Jazz Collective had gathered in the UVSL recording studio — a white concrete building down one of the many dirt side roads. Even with the high-tech equipment, to get clean recordings, the studio had to turn off the air conditioning during recording sessions.

The heat and humidity was unbearable. Between sessions, the musicians resorted to laying on the cool concrete floor and continuously hydrating.

"I thought I was going to pass out during the recording sessions," Boone recalled. "I was thinking, 'when I get back to the United States, I can re-record this. So it doesn't matter if my part is good or not. I'm just going to play with wild abandon and get through it, knowing I can overdub this."

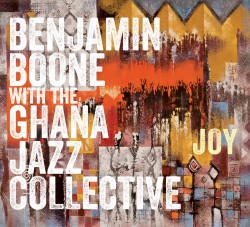

Out of this misery came "Joy." Origin Records released Benjamin Boone's latest studio album in March 2020 featuring the Ghana Jazz Collective — a group of Ghanaian musicians he met during his time as a U.S. Fulbright Scholar at the University of Ghana. "Joy" is available on Amazon, iTunes, Google Play Music, Spotify, and all music platforms and stores. The recording was made possible in part by the Dean's Council Annual Fund.

Months later, back in the U.S., as Boone reviewed the tracks recorded in Ghana, he realized there was an energy on the tracks, which was essential to keep.

"It took me two or three months to decide, no, I think that it's okay. If I don't play perfectly, that's alright because the energy is there," said Boone. "There is no way I could capture the magical musical connection and conversation we had if I was by myself in a studio trying to overdub it. There is no way I could recreate that. So, I kept what we had recorded live. I hope listeners hear how all are playing off of each other and having a musical dialogue."

Finding Joy

In the fall of 2017, Benjamin Boone and his wife Alice Daniel, a former Media, Communications and Journalism (MCJ) professor at Fresno State, and now News Director at Valley Public Radio, received year-long Fulbright Fellowships to Ghana.

Boone had previously studied West African tonal languages in relation to how the blues evolved from slaves transported to the United States. In his scholarship, he planned to collaborate with Ghanaian musicians to bridge the two worlds and explore musical connections between the African origins and current American jazz and blues.

When Boone first arrived in Ghana, he decided that he would spend the first few months observing the local music scene before trying to book any live gigs. But he soon learned that the unspoken protocol for musicians in the U.S. is quite different than for musicians in Ghana.

"I went to the +233 Club one night, and I didn't bring my instrument," said Boone, describing his first visit to the establishment.

In a city of over two million people, the "+233 Club" in Accra, Ghana — "+233" being the country code for international phone calls — features a sizeable well-lit stage on the outdoor patio and is frequented by artists all over the world who stop in to play while they are on tour. Tuesdays are jazz night and regularly features the Ghana Jazz Collective.

Throughout the night, people came up to Boone asking why he didn't bring his instrument.

Boone explained, "In the United States, there is sort-of a protocol where you wait to be asked to play. In Ghana, if you're a musician... you are actually expected to participate, and if you don't participate, it is taken as a little bit of a slight."

With his lesson learned, Boone began by playing a song or two each time he would visit. He then began going almost every Tuesday. It was with the Jazz Collective that he would go on to rent studio time and document his scholarship.

"It's very western to be very self-conscious about what you do. It's very western to be thinking that if you're not perfect or meeting whatever your internal standard is, then you're a failure."

Self-critique and fear of failure, Boone said, is often the primary motivator for musicians to improve in the Western world. But in Ghana, what he found was quite different.

"They are making music out of joy, and they are not judging you the same way that you're being judged in the United States," Boone realized. "There is this level of fun interaction, not judgmental interaction, that happened with those musicians that I don't think I've ever experienced before."

This concept of non-judgmental musicianship permeated live performances, music education, and even society as a whole. Boone had found joy.

The exchange: old is new, new is old

In Western music, the beat and time signatures are generally obvious.

"We will, we will rock you—[boom, boom, clap; boom, boom, clap]. The beat is just so obvious," Boone demonstrated.

In Ghana, different beats, sometimes with different time signatures, are stacked on top of each other to create polyrhythms. The music can be even more complicated when dancers are involved. While the drummers play layers of secondary beats, the dancers move to the primary beat whose silent steps complete the polyrhythm.

"I learned that the primary beat is always in the dance," said Boone. "So even if we would hear something as being the beat, that might not really be the main beat. The beat is in the dance. Even if no one is dancing, they hear the dance in their head and play off of it."

While Boone was excited about learning to play those newfound rhythms on his saxophone, the Ghana Jazz Collective group looked at that as their old music. They felt the cutting-edge music is American style jazz. Both cultures looked to the other for inspiration and growth.

During his second semester in Ghana, Boone realized that despite a rich tradition of American Jazz artists visiting Ghana, there was no formal training available.

While not part of his initial plan under his Fulbright description, Boone realized in the Ghana Jazz Collective, he had found musicians capable of teaching others the American style of jazz. Along with other notable Ghanaian musicians, and a scholar to teach the relationship of jazz to Ghanaian music, Boone went to work establishing a formal training program.

"I wrote a grant for the U.S. Department of State to fund the 'First Annual Ghana National Jazz Workshop Tour,'" said Boone. "I started off leading it, but as the tour went on, I started giving responsibility to the Ghanaians."

By giving them the experience, Boone said they gained the confidence to carry on the tour after he left.

"I think we trained close to 800 Ghanaian musicians and students about the historic linkages between the United States and Ghana, and how that is embedded in jazz," said Boone. "But also, how to improvise in jazz and what the harmonic context is."

As the tour continued, cultural exchange through music began to emerge. Boone said he found his playing incorporated more Ghanaian style.

"Once we bonded on this tour, they were playing some of my music, and I was playing some of their music. How can we document what has transpired in this time?"

It was here the idea to record a CD was born.

Boone explained, "I wanted to document, not only for myself, but try to take the Ghana Jazz Collective and hold it up in the Western European jazz circles and say, 'Look! This cool stuff is going on in Ghana. They are playing the heck out of American jazz. They are amazing musicians and deserve to be listened to and put on the world stage."

A new way of thinking

This gig was important. It would be televised and streamed online. Kofi Annan, the former Secretary-General of the United Nations, along with dozens of dignitaries, would be in attendance. Boone and a group of top Ghanaian traditional musicians who had invited him to play had to audition to be part of the event. The rehearsals were intense, and the seriousness of the occasion was felt among the musicians.

While the group was working on perfecting their material, a young boy walked up with his saxophone.

"He started honking his saxophone beside me like he's trying to imitate what I'm doing," Boone recalls.

He kept quiet about the distraction, but the pattern continued.

"The drummer would leave for a while and another drummer would come and play. It was this revolving cast of people."

This continued with each rehearsal as the musicians prepared for the concert. While Boone still didn't say anything, he was curious about what was happening.

Sometime later, Boone asked the leader of the group, master xylophonist Aaron Bebe Sukura, why he would allow young amateur musicians to rotate in while rehearsing for such an important gig.

"Prof," Sukura said. "How else are they going to learn?"

Boone was stunned at the implication.

"Would that ever happen here?" asked Boone. "It would never happen in any jazz band — even in a rock group. Certainly not in any classical group!"

The concept struck Boone as a core difference in how our respective cultures learn music. Ghanaians are accepting of people learning and of people's imperfections while they are learning. Rather than placing beginners together to play and expecting them to get better, Ghanaians place their beginners with masters. They see musicians, at any level, worthy of being heard without judgment.

Music as diplomacy

"If you're a Fulbright Scholar, you are an employee of the U.S. Department of State and your mission is to make connections with people in other countries, and then to share your experiences with your fellow Americans" said Boone. "So they like for Fulbright Scholars to go to countries other than the host country."

In Ethiopia, the current president had just won the Nobel Peace Prize shortly after he was elected. One tribe had been in power for many years and following the election of the new Prime Minister in 2018, there was a lot of political unrest.

Boone said the State Department wanted him to visit Ethiopia in celebration of Jazz Month — right before the new Prime Minister, Abiy Ahmed, took power.

"There is such a rich history in jazz of social justice," said Boone. "The racism in the United States was addressed through jazz music before it was addressed through other music."

Boone gave a lecture on jazz and social justice and was interviewed on the radio with an audience of about five million people in which he talked about how change can happen through peaceful means.

During his time there, he saw the remnants of political unrest such as roadblocks and smashed buildings.

"What a fascinating time to be in a country where there is this tension. But after [Ahmed] was sworn in and gave a brilliant speech of unification, everything was okay."

Through the eyes of a musician, Boone said he saw the power of diplomacy and how countries work behind the scenes to ensure peaceful transitions of power.

Jazz and social justice

"If you are a musician, you are immediately accepted into Ghanaian culture," said Boone. "Everyone plays music, but they really do hold people who are masters in very, very high regard."

Boone said being a musician gave him an entree into other conversations of philosophy, life in the United States, and politics that otherwise may have been difficult to have. Being an American jazz musician, Boone found even deeper, sometimes uncomfortable, connections that help both cultures come to grips with a complicated past.

"American [jazz] music was created largely by Ghanaian and West African slaves," explained Boone. "So, in talking about the music, you can talk about the horrible circumstances, and you can come to some sort of reconciliation."

Bridging culture through music is a concept Boone hopes to bring back to his students at Fresno State.

"In music, most of the curriculum that our students' study is dead white male Western [European] music. And I look at my students, and I see that they are from all over," said Boone. "So, I actually think that it's a form of colonization to say, 'Western music is the only music that is worthy of study.'"

Boone and professor of music Donald Henriques are now pushing to globalize the curriculum across disciplines, but especially in the Department of Music. He hopes to match the diversity of music taught in the classroom with the diversity of the students by bringing those philosophies, cultures, and ideas into the classroom.

"It's one of the beautiful things about music. It can take you into situations and give you an entree into experiences and cultures that you never would have had if you weren't a musician."

The heat and humidity was unbearable. Between sessions, the musicians resorted to laying on the cool concrete floor and continuously hydrating.

"I thought I was going to pass out during the recording sessions," Boone recalled. "I was thinking, 'when I get back to the United States, I can re-record this. So it doesn't matter if my part is good or not. I'm just going to play with wild abandon and get through it, knowing I can overdub this."

Out of this misery came "Joy." Origin Records released Benjamin Boone's latest studio album in March 2020 featuring the Ghana Jazz Collective — a group of Ghanaian musicians he met during his time as a U.S. Fulbright Scholar at the University of Ghana. "Joy" is available on Amazon, iTunes, Google Play Music, Spotify, and all music platforms and stores. The recording was made possible in part by the Dean's Council Annual Fund.

Months later, back in the U.S., as Boone reviewed the tracks recorded in Ghana, he realized there was an energy on the tracks, which was essential to keep.

"It took me two or three months to decide, no, I think that it's okay. If I don't play perfectly, that's alright because the energy is there," said Boone. "There is no way I could capture the magical musical connection and conversation we had if I was by myself in a studio trying to overdub it. There is no way I could recreate that. So, I kept what we had recorded live. I hope listeners hear how all are playing off of each other and having a musical dialogue."

Finding Joy

In the fall of 2017, Benjamin Boone and his wife Alice Daniel, a former Media, Communications and Journalism (MCJ) professor at Fresno State, and now News Director at Valley Public Radio, received year-long Fulbright Fellowships to Ghana.

Boone had previously studied West African tonal languages in relation to how the blues evolved from slaves transported to the United States. In his scholarship, he planned to collaborate with Ghanaian musicians to bridge the two worlds and explore musical connections between the African origins and current American jazz and blues.

When Boone first arrived in Ghana, he decided that he would spend the first few months observing the local music scene before trying to book any live gigs. But he soon learned that the unspoken protocol for musicians in the U.S. is quite different than for musicians in Ghana.

"I went to the +233 Club one night, and I didn't bring my instrument," said Boone, describing his first visit to the establishment.

In a city of over two million people, the "+233 Club" in Accra, Ghana — "+233" being the country code for international phone calls — features a sizeable well-lit stage on the outdoor patio and is frequented by artists all over the world who stop in to play while they are on tour. Tuesdays are jazz night and regularly features the Ghana Jazz Collective.

Throughout the night, people came up to Boone asking why he didn't bring his instrument.

Boone explained, "In the United States, there is sort-of a protocol where you wait to be asked to play. In Ghana, if you're a musician... you are actually expected to participate, and if you don't participate, it is taken as a little bit of a slight."

With his lesson learned, Boone began by playing a song or two each time he would visit. He then began going almost every Tuesday. It was with the Jazz Collective that he would go on to rent studio time and document his scholarship.

"It's very western to be very self-conscious about what you do. It's very western to be thinking that if you're not perfect or meeting whatever your internal standard is, then you're a failure."

Self-critique and fear of failure, Boone said, is often the primary motivator for musicians to improve in the Western world. But in Ghana, what he found was quite different.

"They are making music out of joy, and they are not judging you the same way that you're being judged in the United States," Boone realized. "There is this level of fun interaction, not judgmental interaction, that happened with those musicians that I don't think I've ever experienced before."

This concept of non-judgmental musicianship permeated live performances, music education, and even society as a whole. Boone had found joy.

The exchange: old is new, new is old

In Western music, the beat and time signatures are generally obvious.

"We will, we will rock you—[boom, boom, clap; boom, boom, clap]. The beat is just so obvious," Boone demonstrated.

In Ghana, different beats, sometimes with different time signatures, are stacked on top of each other to create polyrhythms. The music can be even more complicated when dancers are involved. While the drummers play layers of secondary beats, the dancers move to the primary beat whose silent steps complete the polyrhythm.

"I learned that the primary beat is always in the dance," said Boone. "So even if we would hear something as being the beat, that might not really be the main beat. The beat is in the dance. Even if no one is dancing, they hear the dance in their head and play off of it."

While Boone was excited about learning to play those newfound rhythms on his saxophone, the Ghana Jazz Collective group looked at that as their old music. They felt the cutting-edge music is American style jazz. Both cultures looked to the other for inspiration and growth.

During his second semester in Ghana, Boone realized that despite a rich tradition of American Jazz artists visiting Ghana, there was no formal training available.

While not part of his initial plan under his Fulbright description, Boone realized in the Ghana Jazz Collective, he had found musicians capable of teaching others the American style of jazz. Along with other notable Ghanaian musicians, and a scholar to teach the relationship of jazz to Ghanaian music, Boone went to work establishing a formal training program.

"I wrote a grant for the U.S. Department of State to fund the 'First Annual Ghana National Jazz Workshop Tour,'" said Boone. "I started off leading it, but as the tour went on, I started giving responsibility to the Ghanaians."

By giving them the experience, Boone said they gained the confidence to carry on the tour after he left.

"I think we trained close to 800 Ghanaian musicians and students about the historic linkages between the United States and Ghana, and how that is embedded in jazz," said Boone. "But also, how to improvise in jazz and what the harmonic context is."

As the tour continued, cultural exchange through music began to emerge. Boone said he found his playing incorporated more Ghanaian style.

"Once we bonded on this tour, they were playing some of my music, and I was playing some of their music. How can we document what has transpired in this time?"

It was here the idea to record a CD was born.

Boone explained, "I wanted to document, not only for myself, but try to take the Ghana Jazz Collective and hold it up in the Western European jazz circles and say, 'Look! This cool stuff is going on in Ghana. They are playing the heck out of American jazz. They are amazing musicians and deserve to be listened to and put on the world stage."

A new way of thinking

This gig was important. It would be televised and streamed online. Kofi Annan, the former Secretary-General of the United Nations, along with dozens of dignitaries, would be in attendance. Boone and a group of top Ghanaian traditional musicians who had invited him to play had to audition to be part of the event. The rehearsals were intense, and the seriousness of the occasion was felt among the musicians.

While the group was working on perfecting their material, a young boy walked up with his saxophone.

"He started honking his saxophone beside me like he's trying to imitate what I'm doing," Boone recalls.

He kept quiet about the distraction, but the pattern continued.

"The drummer would leave for a while and another drummer would come and play. It was this revolving cast of people."

This continued with each rehearsal as the musicians prepared for the concert. While Boone still didn't say anything, he was curious about what was happening.

Sometime later, Boone asked the leader of the group, master xylophonist Aaron Bebe Sukura, why he would allow young amateur musicians to rotate in while rehearsing for such an important gig.

"Prof," Sukura said. "How else are they going to learn?"

Boone was stunned at the implication.

"Would that ever happen here?" asked Boone. "It would never happen in any jazz band — even in a rock group. Certainly not in any classical group!"

The concept struck Boone as a core difference in how our respective cultures learn music. Ghanaians are accepting of people learning and of people's imperfections while they are learning. Rather than placing beginners together to play and expecting them to get better, Ghanaians place their beginners with masters. They see musicians, at any level, worthy of being heard without judgment.

Music as diplomacy

"If you're a Fulbright Scholar, you are an employee of the U.S. Department of State and your mission is to make connections with people in other countries, and then to share your experiences with your fellow Americans" said Boone. "So they like for Fulbright Scholars to go to countries other than the host country."

In Ethiopia, the current president had just won the Nobel Peace Prize shortly after he was elected. One tribe had been in power for many years and following the election of the new Prime Minister in 2018, there was a lot of political unrest.

Boone said the State Department wanted him to visit Ethiopia in celebration of Jazz Month — right before the new Prime Minister, Abiy Ahmed, took power.

"There is such a rich history in jazz of social justice," said Boone. "The racism in the United States was addressed through jazz music before it was addressed through other music."

Boone gave a lecture on jazz and social justice and was interviewed on the radio with an audience of about five million people in which he talked about how change can happen through peaceful means.

During his time there, he saw the remnants of political unrest such as roadblocks and smashed buildings.

"What a fascinating time to be in a country where there is this tension. But after [Ahmed] was sworn in and gave a brilliant speech of unification, everything was okay."

Through the eyes of a musician, Boone said he saw the power of diplomacy and how countries work behind the scenes to ensure peaceful transitions of power.

Jazz and social justice

"If you are a musician, you are immediately accepted into Ghanaian culture," said Boone. "Everyone plays music, but they really do hold people who are masters in very, very high regard."

Boone said being a musician gave him an entree into other conversations of philosophy, life in the United States, and politics that otherwise may have been difficult to have. Being an American jazz musician, Boone found even deeper, sometimes uncomfortable, connections that help both cultures come to grips with a complicated past.

"American [jazz] music was created largely by Ghanaian and West African slaves," explained Boone. "So, in talking about the music, you can talk about the horrible circumstances, and you can come to some sort of reconciliation."

Bridging culture through music is a concept Boone hopes to bring back to his students at Fresno State.

"In music, most of the curriculum that our students' study is dead white male Western [European] music. And I look at my students, and I see that they are from all over," said Boone. "So, I actually think that it's a form of colonization to say, 'Western music is the only music that is worthy of study.'"

Boone and professor of music Donald Henriques are now pushing to globalize the curriculum across disciplines, but especially in the Department of Music. He hopes to match the diversity of music taught in the classroom with the diversity of the students by bringing those philosophies, cultures, and ideas into the classroom.

"It's one of the beautiful things about music. It can take you into situations and give you an entree into experiences and cultures that you never would have had if you weren't a musician."

Soundclips

Other Reviews of

"Joy":

JazzdaGama by Raul Da Gama

Jazz Podium (Germany) by WOLFGANG GRATZER

All About Jazz by Chris M. Slawecki

Jazz Weekly by George W Harris

All About Jazz by Chris M. Slawecki

THE MUNRO REVIEW by Donald Munro

JazzTimes by David Whiteis

Amazon by Dr. Debra Jan Bibel

DownBeat by Hobart Taylor

Rochester City Paper (NY) by Ron Netsky

All About Jazz by Dan Bilawsky

Midwest Record by Chris Spector