MUSIC REVIEW BY Donald Munro, THE MUNRO REVIEW

10 INSIGHTS INTO GHANA AND THE MAKING OF BENJAMIN BOONE'S ACCLAIMED NEW ALBUM

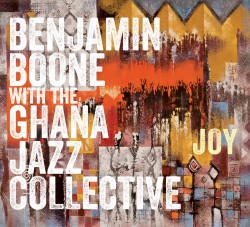

At the moment I am listening to the opening song "The Intricacies of Alice" on Benjamin Boone's "Joy," and the act of rolling that title around my brain gives me, well, joy. Which is just one of many reasons that makes this new album for me so aptly titled.

There's a personal connection: I know Ben's wife, Alice, for whom the song is titled, and as I listen to the tune — described by Dan Bilawsky in his four-star review in "All About Jazz" as "shifting gears with incredible precision while also keeping a fixed eye on melodic clarity" — I can see Alice in my mind, as a journalist, a mom, a spouse, a professor, a woman on a yearlong adventure in Ghana. I can see that little crinkle in her grin when she's amused and the frown when she isn't, and as the music soars, I see a person who is complicated and wonderful.

And in a more general sense, there is my connection as someone who, in uncertain times, needs a little more joy in my life.

"Joy" was recorded long before coronavirus, of course, coming together in 2019 as one of the culminating memories of Boone's stint as a Fulbright scholar in Ghana. The Fresno State professor collided creatively with a cosmopolitan group of brilliant, Accra-based jazz musicians that call themselves the Ghana Jazz Collective. The ensemble includes tenor saxophonist Bernard Ayisa, pianist Victor Dey Jr., bassist Bright Osei, and drummer Frank Kissi.

While laced with unmistakably West African polyrhythms, the music wouldn't sound out of place in Manhattan, Los Angeles, or London, encompassing funk, fusion, R&B, and post-bop idioms.

The album had long been slated for a March 20 release, and Boone decided to go ahead with the plan, even though when the time came, the virus was already disrupting many facets of everyday life.

He told me:

"In one respect, this is really one of the worst times to release an album. It is impossible to book any performances anywhere, and of course the media is mostly covering the horrific pandemic as it well should. People are also totally saturated by all of the information coming at them, so there isn't the bandwidth available for an album release. But in another way, this is the ideal time for this particular album to come out."

The album has been a strong seller, hitting No. 1 on Amazon's Hot Releases in Jazz Fusion list and has been in the Top 100 for radio play in the past two weeks. It also received great reviews. ("Wow, this album is full of power!" said Murf Reeves of WWOZ New Orleans. "I love the dynamics of the songs. I sort of feel like I'm hang-gliding through a mountain range.")

Maybe, Boone says, in some small way, this music can contribute to a feeling of hope, encouragement, and togetherness during this really hard time.

In that spirit, I asked him to compose — using words, not notes — something original for The Munro Review, and he graciously obliged. What follows is a heartfelt testament to a glorious life experience: "10 Insights into Ghana and the making of "Joy."

Read on:

1. SOME LATIN RHYTHMS ARE REALLY GHANAIAN

The Clave rhythm is ubiquitous in Latin music, so, when I first arrived in Ghana and heard the "clave rhythm" in so much of the Ghanaian traditional and popular music, I thought, "Wow - they are influenced by Latin music!"

But then I learned it was the other way around. West African slaves already used this rhythm and brought it to South America, impacting Latin and Afro-Cuban music. Why wasn't it used in North American music? As a scholar at the University of Ghana told me, "The U.S. had a particularly brutal form of slavery designed to erase African culture."

2. WHERE'S THE BEAT?

One of my favorite stories: Around the corner from my office at the University of Ghana there were two open-air areas where dance classes accompanied by about eight percussionists would occur. One day, I heard particularly cool drumming. There were about four independent streams of meter going on, and I sat in my office trying to write it out into music manuscript. After about 20 minutes, I went out to watch the dancers, and my mouth dropped.

What they were doing with their feet wasn't what I had indicated was the main pulse. I stood there trying to figure it out, and the instructor came up and said, "Figured it out yet, Prof?" I said, "No, not yet." He laughed and said to keep trying.

He came over a minute later and I said, "So it's 3 against 4, and the 3 is in the feet, not the 4." He said, "You are learning, Prof!"

From that minute on, I realized I had been mis-hearing several of the traditional tunes I had been learning. What I heard as a main beat was often a secondary beat. The main beat was in the dance, and since I didn't know the dance, I was mis-hearing the music!

Almost every day I was humbled in some significant way, and so I grew exponentially as a person and as a musician.

3. BEING A MUSICIAN IN GHANA AND MUSIC EDUCATION

Music is woven into the fabric of life in Ghana. People just sing to sing. At stores, the pool, and all gatherings, there is music making going on of one kind or another, and of course everyone participates by singing, playing an instrument, or dancing. Music-making is not left to professionals - it is communal and participatory.

For example, I was part of a traditional group made up of master musicians that was playing for an important university event. At the first practice a young saxophonist walked up and tried to imitate what I was doing. The guy couldn't play well and it really distracted me, but of course I said nothing. I noticed people passing by the rehearsal area would come in, play the drums for a while, and then leave. I wasn't even sure who the true members of the group were! This happened at every rehearsal.

Several months later, I asked one of the players about this and he looked at me incredulously and said, "Prof, how else do you expect them to learn?"

It took awhile for this to sink in. Then I saw the beauty in it. Beginners are encouraged to jam with professionals - it isn't expected that they have to be great, or that they play perfectly - that is how they learn! Would that ever happen at a professional string quartet or at a professional jazz rehearsal in the U.S.? No way. Here, all beginners are put into a band together and expected to magically improve. But that isn't how we learn to speak, and it's not the most effective way to learn. What a valuable lesson. Let everyone of all levels make music together joyfully! It has altered how I view education.

4. NO MICS?

On the second day of recording, we had arranged to have some really good mics, but when we got to the studio they hadn't arrived. The studio had no usable mics, and the engineer wanted to reschedule the session. But I was leaving Ghana in TWO days, so that wasn't an option. We called around and about four hours later got someone to bring us some mics. The singer Sandra Huson picked them up on her way to the studio, and so we were able to record.

5. MAGIC BORN OUT OF HEAT EXHAUSTION

It was indescribably hot in the UVSL recording studio where we recorded this album. So hot that Bernard Ayisa (the Ghanaian saxophonist) and I had to lay down on the concrete floor between takes to cool off. The studio did have air conditioning, but it had to be off any time we were recording because of the noise. I don't think I've ever consumed so much water and peed so little in my life! But in spite of that, the musicians were so into the process, so into the "zone," and we were connecting musically so well, that we were having the times of our lives making this music in spite of the heat.

In fact, I think the heat made me play much more freely than I would have otherwise. I knew I couldn't play as technically well as I could under other circumstances, and so I remember thinking to myself "I am just going to go for it and not worry about it. I can always overdub these tracks later when I am back in the U.S." So I played with wild abandon.

But when I was back in the U.S. and heard what I had done, how free I had been, I realized it would be impossible to recapture that energy and connection and shared purpose that we had in Ghana. Needless to say, I didn't do any overdubs!

6. BACKSTORY OF "WITHOUT YOU"

I wrote this song after two friends died unexpectedly, Ed Lund and Colin Walton. It was composed from the perspective of the partner they left behind. In Ghana, I heard Sandra Huson sing, and knew I wanted her to sing this song, but I didn't have the words with me. I kept trying to come up with the words, but it wasn't happening, and I was getting frustrated.

Then I found myself alone in the U.S. Embassy cafeteria. I was overcome with sadness, grief, and loss about leaving Ghana and returning to the US. Then, I imagined how I would feel if my wife had been the one to die tragically, and I was the one left. Tears started streaming down my cheeks. The words flowed.

7. POST-COLONIAL GHANA

Ghana is the first post-colonial African country to be governed by an African, Kwame Nkrumah. The first president intelligently pitted John F. Kennedy against Stalin, and ended up getting the U.S. to build a huge dam, which still provides Ghana a steady hydro-electric power. Ghana is democratic, has less violent crimes that the U.S., scores higher in press freedom, and has greater voter turnout.

8. SLAVE TRADE

Most African Americans in the U.S. can trace their lineage through Ghana - it was the hub where people were brought to be sold. "Slave Castles" - the places slaves were held until they were shipped abroad — are all along the coast of Ghana. We visited one in Cape Coast that ironically had a church built over a huge slave holding area with a narrow shaft in the floor to "allow" the captives to hear the gospel.

9. JUVENILE JUSTICE

One of the Fulbright Scholars staying in our compound was a law professor. Her project was to work with the Ghanaian Supreme Court justices and Parliament on juvenile justice reform. She said they are already light years ahead of the U.S. in this regard. For example, when someone commits a crime, the people believe something prompted the person to do it, and if they can mitigate that force, the person will be OK In essence, they separate the behavior from the person. As such, their system is based on rehabilitation rather than punishment.

10. HOW MUCH DID I LOVE GHANA?

If someone had offered me the option of staying in my role of U.S. Fulbright Scholar for five more years, but I had to give up everything I owned in the U.S., including my house in return, I would have done it in a heartbeat.

Why? Because while in Ghana I could recreate myself. I was able to practice every day and play with musicians who challenged me in ways I'd never been challenged before. I had to learn everything all over again, and after the first three months of cognitive dissonance, I could feel my brain forming new perspectives and pathways.

From trying to imitate traditional xylophone sounds on the sax, to trying to learn to drum (I was awful!), to learning to feel multiple pulses, to playing with pop musicians and the amazing Ghana Jazz Collective, I have never been more creatively stimulated. For whatever reason, in Ghana my self-critic became quieter, fear and self-consciousness began to relax, and I felt for the first time I was fully accepted as a musician.

The Ghanaians I had the privilege of knowing had an appreciation for life, a love of peace, a sense of welcoming, and a caring communal sensibility. What a joyous way to live and to make music!

At the moment I am listening to the opening song "The Intricacies of Alice" on Benjamin Boone's "Joy," and the act of rolling that title around my brain gives me, well, joy. Which is just one of many reasons that makes this new album for me so aptly titled.

There's a personal connection: I know Ben's wife, Alice, for whom the song is titled, and as I listen to the tune — described by Dan Bilawsky in his four-star review in "All About Jazz" as "shifting gears with incredible precision while also keeping a fixed eye on melodic clarity" — I can see Alice in my mind, as a journalist, a mom, a spouse, a professor, a woman on a yearlong adventure in Ghana. I can see that little crinkle in her grin when she's amused and the frown when she isn't, and as the music soars, I see a person who is complicated and wonderful.

And in a more general sense, there is my connection as someone who, in uncertain times, needs a little more joy in my life.

"Joy" was recorded long before coronavirus, of course, coming together in 2019 as one of the culminating memories of Boone's stint as a Fulbright scholar in Ghana. The Fresno State professor collided creatively with a cosmopolitan group of brilliant, Accra-based jazz musicians that call themselves the Ghana Jazz Collective. The ensemble includes tenor saxophonist Bernard Ayisa, pianist Victor Dey Jr., bassist Bright Osei, and drummer Frank Kissi.

While laced with unmistakably West African polyrhythms, the music wouldn't sound out of place in Manhattan, Los Angeles, or London, encompassing funk, fusion, R&B, and post-bop idioms.

The album had long been slated for a March 20 release, and Boone decided to go ahead with the plan, even though when the time came, the virus was already disrupting many facets of everyday life.

He told me:

"In one respect, this is really one of the worst times to release an album. It is impossible to book any performances anywhere, and of course the media is mostly covering the horrific pandemic as it well should. People are also totally saturated by all of the information coming at them, so there isn't the bandwidth available for an album release. But in another way, this is the ideal time for this particular album to come out."

The album has been a strong seller, hitting No. 1 on Amazon's Hot Releases in Jazz Fusion list and has been in the Top 100 for radio play in the past two weeks. It also received great reviews. ("Wow, this album is full of power!" said Murf Reeves of WWOZ New Orleans. "I love the dynamics of the songs. I sort of feel like I'm hang-gliding through a mountain range.")

Maybe, Boone says, in some small way, this music can contribute to a feeling of hope, encouragement, and togetherness during this really hard time.

In that spirit, I asked him to compose — using words, not notes — something original for The Munro Review, and he graciously obliged. What follows is a heartfelt testament to a glorious life experience: "10 Insights into Ghana and the making of "Joy."

Read on:

1. SOME LATIN RHYTHMS ARE REALLY GHANAIAN

The Clave rhythm is ubiquitous in Latin music, so, when I first arrived in Ghana and heard the "clave rhythm" in so much of the Ghanaian traditional and popular music, I thought, "Wow - they are influenced by Latin music!"

But then I learned it was the other way around. West African slaves already used this rhythm and brought it to South America, impacting Latin and Afro-Cuban music. Why wasn't it used in North American music? As a scholar at the University of Ghana told me, "The U.S. had a particularly brutal form of slavery designed to erase African culture."

2. WHERE'S THE BEAT?

One of my favorite stories: Around the corner from my office at the University of Ghana there were two open-air areas where dance classes accompanied by about eight percussionists would occur. One day, I heard particularly cool drumming. There were about four independent streams of meter going on, and I sat in my office trying to write it out into music manuscript. After about 20 minutes, I went out to watch the dancers, and my mouth dropped.

What they were doing with their feet wasn't what I had indicated was the main pulse. I stood there trying to figure it out, and the instructor came up and said, "Figured it out yet, Prof?" I said, "No, not yet." He laughed and said to keep trying.

He came over a minute later and I said, "So it's 3 against 4, and the 3 is in the feet, not the 4." He said, "You are learning, Prof!"

From that minute on, I realized I had been mis-hearing several of the traditional tunes I had been learning. What I heard as a main beat was often a secondary beat. The main beat was in the dance, and since I didn't know the dance, I was mis-hearing the music!

Almost every day I was humbled in some significant way, and so I grew exponentially as a person and as a musician.

3. BEING A MUSICIAN IN GHANA AND MUSIC EDUCATION

Music is woven into the fabric of life in Ghana. People just sing to sing. At stores, the pool, and all gatherings, there is music making going on of one kind or another, and of course everyone participates by singing, playing an instrument, or dancing. Music-making is not left to professionals - it is communal and participatory.

For example, I was part of a traditional group made up of master musicians that was playing for an important university event. At the first practice a young saxophonist walked up and tried to imitate what I was doing. The guy couldn't play well and it really distracted me, but of course I said nothing. I noticed people passing by the rehearsal area would come in, play the drums for a while, and then leave. I wasn't even sure who the true members of the group were! This happened at every rehearsal.

Several months later, I asked one of the players about this and he looked at me incredulously and said, "Prof, how else do you expect them to learn?"

It took awhile for this to sink in. Then I saw the beauty in it. Beginners are encouraged to jam with professionals - it isn't expected that they have to be great, or that they play perfectly - that is how they learn! Would that ever happen at a professional string quartet or at a professional jazz rehearsal in the U.S.? No way. Here, all beginners are put into a band together and expected to magically improve. But that isn't how we learn to speak, and it's not the most effective way to learn. What a valuable lesson. Let everyone of all levels make music together joyfully! It has altered how I view education.

4. NO MICS?

On the second day of recording, we had arranged to have some really good mics, but when we got to the studio they hadn't arrived. The studio had no usable mics, and the engineer wanted to reschedule the session. But I was leaving Ghana in TWO days, so that wasn't an option. We called around and about four hours later got someone to bring us some mics. The singer Sandra Huson picked them up on her way to the studio, and so we were able to record.

5. MAGIC BORN OUT OF HEAT EXHAUSTION

It was indescribably hot in the UVSL recording studio where we recorded this album. So hot that Bernard Ayisa (the Ghanaian saxophonist) and I had to lay down on the concrete floor between takes to cool off. The studio did have air conditioning, but it had to be off any time we were recording because of the noise. I don't think I've ever consumed so much water and peed so little in my life! But in spite of that, the musicians were so into the process, so into the "zone," and we were connecting musically so well, that we were having the times of our lives making this music in spite of the heat.

In fact, I think the heat made me play much more freely than I would have otherwise. I knew I couldn't play as technically well as I could under other circumstances, and so I remember thinking to myself "I am just going to go for it and not worry about it. I can always overdub these tracks later when I am back in the U.S." So I played with wild abandon.

But when I was back in the U.S. and heard what I had done, how free I had been, I realized it would be impossible to recapture that energy and connection and shared purpose that we had in Ghana. Needless to say, I didn't do any overdubs!

6. BACKSTORY OF "WITHOUT YOU"

I wrote this song after two friends died unexpectedly, Ed Lund and Colin Walton. It was composed from the perspective of the partner they left behind. In Ghana, I heard Sandra Huson sing, and knew I wanted her to sing this song, but I didn't have the words with me. I kept trying to come up with the words, but it wasn't happening, and I was getting frustrated.

Then I found myself alone in the U.S. Embassy cafeteria. I was overcome with sadness, grief, and loss about leaving Ghana and returning to the US. Then, I imagined how I would feel if my wife had been the one to die tragically, and I was the one left. Tears started streaming down my cheeks. The words flowed.

7. POST-COLONIAL GHANA

Ghana is the first post-colonial African country to be governed by an African, Kwame Nkrumah. The first president intelligently pitted John F. Kennedy against Stalin, and ended up getting the U.S. to build a huge dam, which still provides Ghana a steady hydro-electric power. Ghana is democratic, has less violent crimes that the U.S., scores higher in press freedom, and has greater voter turnout.

8. SLAVE TRADE

Most African Americans in the U.S. can trace their lineage through Ghana - it was the hub where people were brought to be sold. "Slave Castles" - the places slaves were held until they were shipped abroad — are all along the coast of Ghana. We visited one in Cape Coast that ironically had a church built over a huge slave holding area with a narrow shaft in the floor to "allow" the captives to hear the gospel.

9. JUVENILE JUSTICE

One of the Fulbright Scholars staying in our compound was a law professor. Her project was to work with the Ghanaian Supreme Court justices and Parliament on juvenile justice reform. She said they are already light years ahead of the U.S. in this regard. For example, when someone commits a crime, the people believe something prompted the person to do it, and if they can mitigate that force, the person will be OK In essence, they separate the behavior from the person. As such, their system is based on rehabilitation rather than punishment.

10. HOW MUCH DID I LOVE GHANA?

If someone had offered me the option of staying in my role of U.S. Fulbright Scholar for five more years, but I had to give up everything I owned in the U.S., including my house in return, I would have done it in a heartbeat.

Why? Because while in Ghana I could recreate myself. I was able to practice every day and play with musicians who challenged me in ways I'd never been challenged before. I had to learn everything all over again, and after the first three months of cognitive dissonance, I could feel my brain forming new perspectives and pathways.

From trying to imitate traditional xylophone sounds on the sax, to trying to learn to drum (I was awful!), to learning to feel multiple pulses, to playing with pop musicians and the amazing Ghana Jazz Collective, I have never been more creatively stimulated. For whatever reason, in Ghana my self-critic became quieter, fear and self-consciousness began to relax, and I felt for the first time I was fully accepted as a musician.

The Ghanaians I had the privilege of knowing had an appreciation for life, a love of peace, a sense of welcoming, and a caring communal sensibility. What a joyous way to live and to make music!

Soundclips

Other Reviews of

"Joy":

JazzdaGama by Raul Da Gama

Jazz Podium (Germany) by WOLFGANG GRATZER

All About Jazz by Chris M. Slawecki

Jazz Weekly by George W Harris

All About Jazz by Chris M. Slawecki

JazzTimes by David Whiteis

Fresno State College of Arts & Humanities by Benjamin Kirk

Amazon by Dr. Debra Jan Bibel

DownBeat by Hobart Taylor

Rochester City Paper (NY) by Ron Netsky

All About Jazz by Dan Bilawsky

Midwest Record by Chris Spector