MUSIC REVIEW BY THOMAS STAUDTER, New York Times

A Hard Working Jazzman

ON and off the bandstand, Giacomo Gates fits the profile of the suave, cool jazz singer with ease. He favors stylish dark clothes for his tall, broad-shouldered frame, exudes a mixture of confidence and charm typical of a professional entertainer and casually drops hepcat slang into conversation, saying ''I'm gone,'' for instance, instead of ''goodbye.''

The unique ring he wears on the pinky of his right hand, made from a big gold nugget, tells another story altogether, though. From 1975 to 1988 Mr. Gates, now 54, worked as a heavy equipment operator in Alaska, building roads mostly, during the construction of the oil pipeline. It was a rough-and-tumble frontier existence, he said, and the ring was bought with one of his bigger paychecks.

But for the past 15, Mr. Gates, a Bridgeport native, has seen his popularity rise steadily in the jazz world, and today he is regarded to be one of the leading practitioners of vocalese, a challenging mode of singing a lyric that has been matched to a previously recorded bebop instrumental solo, at a tongue-twister pace.

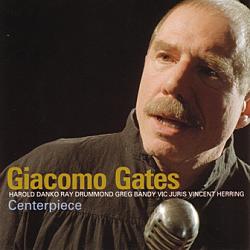

Mr. Gates gained more attention in the fall with the release of his third album, Centerpiece, which reached No. 12 on the National Jazz Playlist chart. Since then, offers for club and concert dates have been rolling in, and he has even been booked already for some shows in 2006.

''Actually, what gasses me the most is that the musicians I'm working with -- all world-class people -- look like they're having a great time when we're playing, and they're telling me that my music is solid and refreshing,'' said Mr. Gates. ''The material is different from what a lot of other cats are doing, and yet audiences are loving it. This is the kind of validation that I really appreciate.'' At a recent appearance at One Station Plaza in Peekskill, N.Y., Mr. Gates showed he knows how to win over an audience. Accompanied by a guitarist and a bassist, he started his set with ''Lullaby of Birdland,'' written as an instrumental in the 1950's by the pianist George Shearing but now featuring several stanzas of lyrics written by Mr. Gates extolling the history of the famed Manhattan jazz club. Next up was Bobby Troup's novelty tune, ''Hungry Man,'' a food-filled travelogue of

where the singer will go around the country for different delicacies, which elicited chuckles from the audience of 50 or so. Then, during a cover of

Cole Porter's ''You'd Be So Nice to Come Home To,'' Mr. Gates supplied a vocalized virtuoso ''trombone'' solo that brought the house down.

While a number of current jazz artists include or incorporate vocalese in their singing style -- Bobby McFerrin, Al Jarreau and the vocal group known as the Manhattan Transfer are probably the best known -- its inherent difficulties ensure that the club of adherents will be somewhat exclusive.

Jon Hendricks, a progenitor of vocalese in the 1950's, said in a phone call from Los Angeles (where he was set to receive a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Grammys) that because the vocal style is just a generation old, singers are still trying to figure out its intricacies.

''Young folks are taking up vocalese, representing their own generation and helping to broaden the audience for the music, and Giacomo is among

those singers and prominently so,'' said Mr. Hendricks, 83 and living in Toledo, Ohio. ''Not many people can master this music, but Giacomo has. He's an important man.''

The only child of a dressmaker and a welder with a penchant for big band jazz, Mr. Gates - he changed his name from Agostini when he started performing -- learned guitar and then took tap dancing lessons for several years. By the age of 10, he said, he was listening to singers like Cab

Calloway and Jimmy Rushing as his peers swooned over Elvis Presley.

A love of the outdoors and physical labor led him to drop out of what was then Norwalk Technical College and become a construction worker.

Mr. Gates moved to Fairbanks, Alaska, in 1975, and soon he was working farther north on major projects spurred by the oil boom. But he never lost

his love for music, and with lots of money in his pocket he started buying jazz records by the dozens and studying them. Intrigued by vocalese, Mr. Gates began writing lyrics, and before long he was ''sitting in'' at nightclubs and singing.

Mr. Gates would probably still be in Alaska, he said, if he had not met the late jazz writer Grover Sales at a clinic for vocalists at the Fairbanks

Summer Arts Festival in 1988. Mr. Sales recognized his talent and persuaded him to move back east right away to pursue jazz, said Mr. Gates, which he did. ''Having someone like Grover to push me early on made me realize that I

had something special,'' Mr. Gates said recently over lunch at Pizza Time, his favorite pizza parlor in town.

Back in Bridgeport Mr. Gates tried to continue working construction while performing at night, but he finally decided to focus on music.

He moved back to his childhood home in 1998 to care for his mother -- she died two years later -- and he still lives in the small two-bedroom Cape

Cod in the Lake Forest section. It is an impeccably neat bachelor pad cluttered only by books, jazz CD's and weight-lifting equipment.

As much as he relishes any opportunity to perform, Mr. Gates said teaching had become important, and for the past several years he has taught classes and private students at Wesleyan University, the Hartford Conservatory of Music and the Neighborhood Music School in New Haven. His

growing renown has also brought in offers to lead the kind of vocal clinic where his own promise was first detected, and he has made three trips back

to Fairbanks since 1999 to work with students there.

Last week Mr. Gates visited with two jazz classes at American University in Washington before playing a gig that evening, and the students

benefited greatly, said Dr. William Smith, a music professor and jazz ensemble director at the school.

''One of the main things the students were able to hear was how important the intonation and technique Giacomo uses is to telling the story

in each tune,'' said Dr. Smith. ''He weaved together his life experiences and music in a way that was really eye-opening for a lot of the students.''

ON and off the bandstand, Giacomo Gates fits the profile of the suave, cool jazz singer with ease. He favors stylish dark clothes for his tall, broad-shouldered frame, exudes a mixture of confidence and charm typical of a professional entertainer and casually drops hepcat slang into conversation, saying ''I'm gone,'' for instance, instead of ''goodbye.''

The unique ring he wears on the pinky of his right hand, made from a big gold nugget, tells another story altogether, though. From 1975 to 1988 Mr. Gates, now 54, worked as a heavy equipment operator in Alaska, building roads mostly, during the construction of the oil pipeline. It was a rough-and-tumble frontier existence, he said, and the ring was bought with one of his bigger paychecks.

But for the past 15, Mr. Gates, a Bridgeport native, has seen his popularity rise steadily in the jazz world, and today he is regarded to be one of the leading practitioners of vocalese, a challenging mode of singing a lyric that has been matched to a previously recorded bebop instrumental solo, at a tongue-twister pace.

Mr. Gates gained more attention in the fall with the release of his third album, Centerpiece, which reached No. 12 on the National Jazz Playlist chart. Since then, offers for club and concert dates have been rolling in, and he has even been booked already for some shows in 2006.

''Actually, what gasses me the most is that the musicians I'm working with -- all world-class people -- look like they're having a great time when we're playing, and they're telling me that my music is solid and refreshing,'' said Mr. Gates. ''The material is different from what a lot of other cats are doing, and yet audiences are loving it. This is the kind of validation that I really appreciate.'' At a recent appearance at One Station Plaza in Peekskill, N.Y., Mr. Gates showed he knows how to win over an audience. Accompanied by a guitarist and a bassist, he started his set with ''Lullaby of Birdland,'' written as an instrumental in the 1950's by the pianist George Shearing but now featuring several stanzas of lyrics written by Mr. Gates extolling the history of the famed Manhattan jazz club. Next up was Bobby Troup's novelty tune, ''Hungry Man,'' a food-filled travelogue of

where the singer will go around the country for different delicacies, which elicited chuckles from the audience of 50 or so. Then, during a cover of

Cole Porter's ''You'd Be So Nice to Come Home To,'' Mr. Gates supplied a vocalized virtuoso ''trombone'' solo that brought the house down.

While a number of current jazz artists include or incorporate vocalese in their singing style -- Bobby McFerrin, Al Jarreau and the vocal group known as the Manhattan Transfer are probably the best known -- its inherent difficulties ensure that the club of adherents will be somewhat exclusive.

Jon Hendricks, a progenitor of vocalese in the 1950's, said in a phone call from Los Angeles (where he was set to receive a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Grammys) that because the vocal style is just a generation old, singers are still trying to figure out its intricacies.

''Young folks are taking up vocalese, representing their own generation and helping to broaden the audience for the music, and Giacomo is among

those singers and prominently so,'' said Mr. Hendricks, 83 and living in Toledo, Ohio. ''Not many people can master this music, but Giacomo has. He's an important man.''

The only child of a dressmaker and a welder with a penchant for big band jazz, Mr. Gates - he changed his name from Agostini when he started performing -- learned guitar and then took tap dancing lessons for several years. By the age of 10, he said, he was listening to singers like Cab

Calloway and Jimmy Rushing as his peers swooned over Elvis Presley.

A love of the outdoors and physical labor led him to drop out of what was then Norwalk Technical College and become a construction worker.

Mr. Gates moved to Fairbanks, Alaska, in 1975, and soon he was working farther north on major projects spurred by the oil boom. But he never lost

his love for music, and with lots of money in his pocket he started buying jazz records by the dozens and studying them. Intrigued by vocalese, Mr. Gates began writing lyrics, and before long he was ''sitting in'' at nightclubs and singing.

Mr. Gates would probably still be in Alaska, he said, if he had not met the late jazz writer Grover Sales at a clinic for vocalists at the Fairbanks

Summer Arts Festival in 1988. Mr. Sales recognized his talent and persuaded him to move back east right away to pursue jazz, said Mr. Gates, which he did. ''Having someone like Grover to push me early on made me realize that I

had something special,'' Mr. Gates said recently over lunch at Pizza Time, his favorite pizza parlor in town.

Back in Bridgeport Mr. Gates tried to continue working construction while performing at night, but he finally decided to focus on music.

He moved back to his childhood home in 1998 to care for his mother -- she died two years later -- and he still lives in the small two-bedroom Cape

Cod in the Lake Forest section. It is an impeccably neat bachelor pad cluttered only by books, jazz CD's and weight-lifting equipment.

As much as he relishes any opportunity to perform, Mr. Gates said teaching had become important, and for the past several years he has taught classes and private students at Wesleyan University, the Hartford Conservatory of Music and the Neighborhood Music School in New Haven. His

growing renown has also brought in offers to lead the kind of vocal clinic where his own promise was first detected, and he has made three trips back

to Fairbanks since 1999 to work with students there.

Last week Mr. Gates visited with two jazz classes at American University in Washington before playing a gig that evening, and the students

benefited greatly, said Dr. William Smith, a music professor and jazz ensemble director at the school.

''One of the main things the students were able to hear was how important the intonation and technique Giacomo uses is to telling the story

in each tune,'' said Dr. Smith. ''He weaved together his life experiences and music in a way that was really eye-opening for a lot of the students.''

Soundclips

Other Reviews of

"Centerpiece":

Berman Music Review by Tom Ineck

All About Jazz/New York by Elliott Simon

Portfolio Weekly by Jim Newsom

Kansas City Jazz by Tom Ineck

Espresso Jazz by Richard Mayer

L.A. Jazz Scene by Scott Yanow

Stamford Advocate by Ray Hogan

Hartford Courant by Owen McNally

New Jersey Jazz by Joe Lang

In Tune International by Dan Singer

All About Jazz/New York by Elliott Simon

Jazz Times by Christopher Loudon

Los Angeles Daily News by Glenn Whipp

All About Jazz by Jim Santella

JazzReview.com by Don Williamson